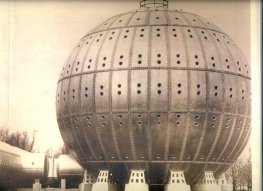

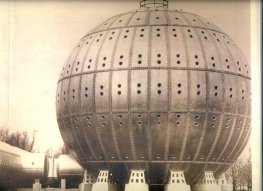

Monster Steel Ball Forms Air Cure Hospital

What was it?

Basically, a huge hyperbaric chamber, 64 feet in diameter and 5 stories tall,

where patients stayed for up to two weeks under increased atmospheric pressure.

Who built it?

In the 1920s Dr. Orval J. Cunningham was a leading exponent of hyperbaric therapy. In the

mid-1920s, he operated the then largest hyperbaric chamber in existence, in Kansas City. An industrial

tycoon, H.H. Timken, heard about this work and gave Cunningham $1,000,000 to build what would

end up being the largest hyperbaric chamber ever constructed. Timken's industry, ball bearings,

was based in Canton, Ohio, but the chamber was built in Cleveland, to Cunningham's specifications.

While in existence it was known as the "Timken Tank" and the "Cunningham Sanitarium."

What did it do?

Air was pressurized (probably in the large tube-like apparatus to left of sphere)

and pumped into the air-tight sphere, so that occupants inhaled air at 30 pounds per square inch.

This is double normal sea level air pressure of 14.7 psi. The theory was that the pressurized air,

by providing double the normal oxygen concentration, would alleviate many diseases

(wrongly attributed) to anaerobic bacteria, such as some cancers, diabetes, pernicious

anemia, and others.

Did it work?

The claims for this and other chambers of the era were entirely specious. There was not

a shred of scientific evidence that the chambers cured any of the diseases claimed to be

helped by Dr. Cunningham. The American Medical Association severely challenged his claims.

In May, 1928 (while the tank was under construction), the AMA Journal published a

critical review

of Dr. Cunningham's treatment. Although not stated in the AMA review, the

extra oxygen afforded by the high atmospheric pressure could just as easily -- and far

more cheaply -- have been delivered from a tank of pressurized oxygen at ordinary

air pressure (a therapy certainly available in the 1920s, though not widely used).

In any case, the Cunningham Steel Ball fell into disrepute, and was no longer used for

hyperbaric therapy after a few short years.

What happened to it?

According to an article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer the Steel Ball "was sold

a few times in the mid-1930s and the ground was bought by the Cleveland Catholic Diocese

in 1941 after the bulding was no longer used. The steel ball was dismantled and

sold for scrap metal during World War II." This event did not go unnoticed by the AMA,

which published an

editorial comment

on April 11, 1942.

What is on the site today?

St. Joseph's High School, built in 1952 (18485 Lake Shore Blvd., Cleveland).

What happened to the field of hyperbaric therapy after the Cunningham Steel Ball?

The whole field fell into some disrepute. Then in 1939 the Navy began treating

divers suffering decompression sickness with hyperbaric oxygen therapy; this was

different than all the previous uses of hyperbaric therapy, since it compressed pure oxygen.

Dr. Cunningham's Steel ball, and all previous hyperbaric chambers, used only compressed

air which, as pointed out above, was no better than just using oxygen from a tank

at the patient's bedside.

Apart from Navy use, however, hyperbaric therapy - with air or pure oxygen - was not on any scientific basis, except for a brief period in the mid-1950s when it was used for open heart surgery. However, cardiac bypass machines soon eliminated the need for hyperbaric oxygen therapy in this situation, and the field was again taken over by practitioners with unfounded claims (except in the Navy and a group doing research in the field). In the mid-1970s, the Undersea & Hyperbaric Medical Society -- an organization made up largely of Navy and ex-Navy physicians -- systematically reviewed all the available scientific evidence for hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO). UHMS came up with a list of conditions for which HBO was likely beneficial (and a much larger list for which it was not). The UHMS list was accepted by insurance providers, including Medicare. Subsequently, UHMS became the scientific arbiter of indications for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. HBO is now accepted for treatment in a small group of specific disorders (see What are the Clinically Accepted Indications?).

How is HBO given today?

HBO is usually delivered in a

monoplace chamber,

big enough for a single patient. A few hospitals and specialized centers

around the world have a

multi-place chamber,

which is big enough for several patients and an attendant.

However, there are no longer any chambers the size of Dr. Cunningham's

grandiose experiments in the 1920s.