Sleep Apnea

Sleep Apnea Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Clinical Professor of Medicine

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland

Board Certified in Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine

Sleep Home Page / Internet Sleep Links / Books about sleep disorders (with links to Amazon.com) / Drugs for Sleep & Awake / Index of Dr. Martin's web sites

- Poor patient tolerance/compliance. The patient is capable of using the

machine, but finds it too discomforting or bothersome;

- Inability to use the machine. The patient is willing but

simply unable to strap it on every night.

This is often a problem with elderly and demented patients;

- Inadequate or no insurance reimbursement. The patient is willing, but because of lack of proper insurance (e.g., requirement of co-pay which the patient can't afford), or no insurance, or loss of insurance, the machine is not available.

Introduction

Life Style Changes

Body Position

Nasal Sprays

Nasal Valve Dilators

Oral Sprays

Dental Appliances

CPAP

Provent therapy

Upper Airway Surgery

Introduction

Snoring is the most common sleep complaint, occurring in about half of middle-aged men, and a third of middle-aged women. While snoring is almost always present in people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), only a small percentage of snorers (perhaps 10%) have OSA. Thus snoring is a "sign" of OSA, but by itself is not diagnostic of OSA.

Assuming both snoring and OSA are present in someone, treatment of just the snoring does not treat the OSA. Snoring is like the 'smoke' of a fire. If you get rid of the smoke the fire can still rage on. However, effective treatment of OSA will usually also improve (or eradicate) the snoring.

Therapy for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea can range from the simple and inexpensive (life style changes) to the costly and complex (surgery). If the goal is simply to treat the snoring, then lifestyle changes, nasal sprays and/or nasal dilators can be tried; if they don't work, and snoring is particularly severe, then surgery on the throat is a last resort option.

For OSA to be diagnosed, that condition first must be formally diagnosed with a sleep study. After diagnosis, treatment will usually involve either continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP, by far the most common therapy), surgery (much less commonly used), or a dental appliance that is shaped like a mouth guard (rarely used compared to CPAP). Life style changes (weight reduction, stop smoking, reduce/eliminate alcohol) should also take place where appropriate.

As a practical matter, virtually all patients with diagnosed OSA are offered CPAP as first line therapy. A dental appliance or throat surgery, while highly effective in some patients, are each considered second line therapy; they are employed when CPAP is either not accepted by the patient or is accepted and fails.

Life Style Changes

SUMMARY: The major life style conditions contributing to snoring and obstructive sleep apnea are obesity, smoking, and excessive alcohol use. To the extent these conditions can be improved, snoring and OSA should also improve.

Obesity is an important risk factor for snoring and OSA. This is because the excess weight is also distributed as fat in the throat area, increasing the risk of airway closure during sleep (when the surrounding muscles tend to relax). Rather substantial amounts of weight loss are usually required to produce significant in OSA, on the order of 20%-30% of body weight. For most obese patients, this much weight reduction is very difficult.

What's overweight? This is now based on a calculation called body mass index or BMI. BMI is your weight in kg divided by height in "meters squared." You don't have to do the math, as BMI calculators easily do it for you. Don't be shocked by the stringent criteria for "overweight" and "obesity."

BMI

Underweight <18.5

Normal 18.5 - 24.98

Overweight 25 - 29.9

Obese >30

Generally, the greater the BMI the more likely will the person snore and have sleep related symptoms. Not only is obesity a major risk factor for OSA, but given the diagnosis of OSA, the greater the weight the worse the symptoms. The silver lining of this observation is that the more symptoms the patient has from OSA, the more likely they will benefit from therapy, particularly nasal CPAP. (See "The number of symptoms present at the time of diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea, and symptom response rate, increased as body mass index increases." Pisani, et. al. Chest Supplement, Vol. 122, October, 2002; page 127S.)

To date drugs have not been successful in allowing weight reduction. (In the past drugs such as Fenfluramine were prescribed for the treatment of obesity. A rare complication of prolonged use of this and similar drugs is a condition called Pulmonary Hypertension. This condition can be fatal and there is no effective treatment apart from heart-lung transplantation. For this reason the drug is no longer used.)

Increasingly used in cases of severe obesity is bariatric surgery. There are several bariatric procedures for weight reduction, but the most common is gastric stapling. Gastric stapling makes the stomach pouch smaller than normal, and can result in dramatic weight loss. Once achieved, this should lead to great improvement in OSA. However, the operation should only be performed by surgeons who do them routinely, and at centers where there is a team available for pre-op evaluation and post op care. There can be numerous medical complications.

Smoking is another important factor. Cigarette smoke irritates the throat, causes chronic inflammation, and can perpetuate any tendency to air flow obstruction. There are a number of drugs on the market to help people quit smoking, listed below.

Drugs for Smoking Cessation

Drug |

Adverse effects |

Dose |

Cost per day (typical daily dose) |

Cost per recommended course of therapy |

NICOTINE GUM (OTC)

|

Dyspepsia, jaw ache |

max 30 cigarettes/day of 2-mg gum

|

$6.25/10 (2 mg)

|

$563/3 months |

NICOTINE INHALER

|

Throat irritation, coughing |

6 - 16 cartridges/day |

$10.94/10 cartridges |

$985/3 months |

NICOTINE NASAL SPRAY

|

Nasal and/or throat irritation, rhinorrhea, sneezing, coughing |

8 - 40 doses/day |

$5.40/12 doses |

$486/3 months |

NICOTINE PATCH (OTC) |

Local skin reaction |

21 mg/24 hours (4 weeks)

|

$3.50 - $4.50/patch |

$240/2 months |

SUSTAINED-RELEASE BUPROPION

|

Dry mouth, agitation, headaches, dizziness, insomnia; contraindicated in seizure disorder |

150 mg once daily for 3 days, then 150 mg twice daily |

$3.33/2 (150 mg) |

$300/3 months patients |

VERENICLINE

|

Nausea, constipation, bad dreams |

3-month course, staring at 0.5 mg tablet a day and building up dose |

varies; @ $100/month |

@300/3 months |

Unfortunately, success rates for quitting smoking are of the order of 10 - 20%, even with the best programs. It takes persistence and determination to quit. See the NIH web site for more information on smoking cessation. For a commercially-sponsored site with some useful information, see About.com - Smoking Cessation.

Finally, alcohol can exacerbate snoring and OSA. Alcohol, particularly before bedtime, increases airway muscle relaxation and sedation during sleep, thereby aggravating any tendency to snoring and sleep apnea. Of course, like smoking and obesity, sleep is only one situation made worse by excessive alcohol intake. The daily drinker risks conditions like liver disease and stomach ulcers, as well as aggravating snoring and OSA.

Sleep hygiene is also important. This means going to bed at a reasonable time and getting a good night's sleep without interruption. Factors that can affect sleep include newborn infants, pets (particularly large dogs), phone interruptions, and over medication (particularly pain medication and psychiatric medications). I've seen many patients referred for a "sleep study" when what they really need is just better sleep hygiene. A poor night's sleep - for whatever reason - can worsen snoring and OSA on the following night.

Body Position

SUMMARY: Snoring and OSA are usually worse when sleeping on your back.

The supine position is worse for snoring/OSA because gravity promotes collapse of the soft palate and the tongue, especially during deep sleep when the muscles are most relaxed. A common complaint of patients is that their bed partners are always poking them in their side. For patients with OSA who are very obese, sleeping with the trunk elevated at 30 degrees relieves the pressure on the diaphragm from the abdomen and improves the patency of the upper airway. This measure alone can reduce the severity of OSA in these very obese patients by ~ 20%. Some patients have developed the habit of sleeping face down. However, this can cause a strain on the neck and lower back.Nasal Sprays

SUMMARY: Blocked nasal passages can aggravate snoring and OSA. Nasal sprays may improve blocked passages.

Blocked nasal passages, per se, are not the cause of obstructive sleep apnea. This is because an otherwise normal person can breathe through his/her mouth. However, the nasal passages are an important part of the upper airway, and their blockage -- whether through a deviated septum, swelling, or excess mucus -- can aggravate any tendency to snoring or obstructive sleep apnea. For example, if there is a tendency for the tongue to fall back of the throat, and the nasal passages are blocked, then obstructive apnea can be aggravated. People with excess mucus often benefit from using nasal sprays. Note that long term use of over-the-counter nasal sprays can lead to side effects, including becoming simply ineffective. NASAL SPRAYS ARE NOT EFFECTIVE FOR SLEEP APNEA.

Nasal Valve Dilators

SUMMARY: Nasal valve dilators are simple mechanical aids to help keep open the nasal passages.

There are two kinds of nasal valve dilators. The first kind is an adhesive strip that is placed over the bridge of the nose at bedtime. These strips cost about $5 for a box of 12, and cannot be reused. Common problems with using these strips include irritation of the skin and the strips coming off in the middle of the night. NASAL STRIPS ARE NOT EFFECTIVE FOR SLEEP APNEA.The second type of nasal valve dilator is a springy piece of plastic that is wider at the ends. The ends are actually inserted into the nostrils. Examples on the market are Nose Works and Nozovent. These dilators cost about $15 for two, and have to be replaced every few months. They can be rather uncomfortable and may irritate the inside lining of the nose.

In one well-conducted medical study of Nozovent (Chest 2000; vol. 118, p. 587), Nozovent decreased the bed partner's perception of snoring in some patients, but the device had no effect on sleep apnea. Thus such a device is worth trying for snoring alone. Patients that benefit usually have small nostrils that collapse easily with sniffing. NASAL DILATORS ARE NOT EFFECTIVE FOR SLEEP APNEA.

Oral Sprays

SUMMARY: Oral sprays are over the counter moisteners promoted to help snoring.

Oral sprays for snoring are heavily promoted, over-the-counter products. A list of many of these sprays can be found at Sprays to Stop Snoring.

These sprays moisten the back of the throat, and may or may not help snorers (the ads tend to be all hype, typical of patent medicines of the 19th and early 20th century). However effective an oral spray may be for snoring, NONE IS EFFECTIVE FOR TREATING SLEEP APNEA.

Dental Appliances

SUMMARY: Dental appliances are worn in the mouth while sleeping; depending on the design, they may help alleviate snoring and/or OSA.

For pictures of dental appliances, see:

Vancouver Sleep & Breathing Center

Mandibular Advancement Appliances

A dental appliance is a small plastic device, fashioned by a dentist, to fit your teeth and jaw. Dental appliances have been used to treat grinding of the teeth and temporomandibular joint problems for years. In the past decade they have gained acceptance for treating some people with snoring and/or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Snoring occurs when there is excessive crowding of the air passage during sleep. As the person breathes, a vibration occurs in the tissues of the throat that produces the snoring noise. The main culprits are the soft palate and the tongue. A dental appliance can serve to pull the jaw and tongue forward and thereby open up the air passage. In a patient with OSA, this has the added benefit of allowing air to flow more freely.

Dental appliances work in one of three ways:

a) by holding the tongue forward

b) by lifting a drooping soft palate

c) by bringing the lower jaw forward

Applicances that work by a) and b) are fixed devices, used mainly for snoring. Devices employing c) are called mandibular advancement applicances (MAPs). MAPs are the most effective for OSA. Using a simple screw device, they can be adjusted nightly over time. In this way the lower jaw can gradually be brought forward to a new and permanent position. By moving the lower jaw forward, the back of the throat 'opens up'.

Everyone's jaw/throat structure is different, so these 'mandibular advancement' require proper fitting. Fitting is not done by most dentists, so the candidate for a dental appliance needs referral to a specialist. Consult the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine web site for specialists in your area. Custom-fitted dental appliances can cost anywhere from several hundred dollars to over $2000.

Studies have confirmed that a well-made, well-fitted dental appliance can reduce or eliminate snoring, and relieve symptoms related to OSA. However, there are some side effects and, as with CPAP, some patients do quit using the device after it is prescribed. See:

A randomized, controlled

study of a mandibular advancement splint for obstructive sleep apnea.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001 May;163(6):1457-61.

Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in

obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, controlled trial.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002 Sep 1;166(5):743-8.

Mandibular advancement splint improves

indices of obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring but side effects are common.

N Z Med J 2002 Jun 21;115(1156):289-92.

Oral Appliance

Therapy Reduces Blood Pressure in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: a Randomized, Controlled Trial

Sleep 2004;27:934-41.

CPAP Therapy

SUMMARY: Continuous positive airway pressure, delivered via a tight-fitting nasal mask, is the most effective and efficient treatment of OSA.

CPAP or Continuous Positive Airway Pressure, is a method of applying positive pressure to the upper airway to prevent it from collapsing during sleep. 'Positive pressure' is the pressure inside a balloon when it is blown up; it is pressure greater than the surrounding, or ambient air pressure. Air at a higher pressure than ambient will travel to any region that has a lower air pressure; hence when positive air pressure is pushed through the nose, it travels down the throat where the air pressure is lower. As a result, the air flows from the nose down into the lungs and keeps the upper airway from collapsing during sleep.

All this is accomplished via a 'CPAP' mask that fits over the nose, so air can't escape around the nose. The mask is connected via a hose to a small pump -- the CPAP machine -- which plugs into a standard electrical socket. Thus the CPAP machine or "pump" functions like any other small electrical appliance.

Picture of man with CPAP mask. The hose is attached to machine which sends air under pressure with each breath, to keep the airway open.

CPAP works, and is now the standard therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. For a scientific review see Practice Parameters for the Use of Continuous and Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure Devices to Treat Adult Patients With Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders , in the medical journal Sleep, Vol. 29 (2006), pages 375-380.

The history of CPAP is interesting. It was first reported for sleep apnea in 1981 (Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet 1981;1:862-5.) However, it was not until the mid 1980s that CPAP began to be accepted for sleep apnea. Since then there have been steady technologic improvements in three areas: the CPAP machine itself, the nasal mask and strap arrangements, and humidification. The machines have become much smaller and quieter. The masks have been made far more comfortable for the user, and strap arrangements have improved. Finally, for patients with some nasal problems, heated humidification added to the system has increased compliance.

Another advance is the gradual acceptance among payors that CPAP works, so that now CPAP is usually covered by health insurance. However, there are still issues in this area. One is the amount of coverage; some companies require a co-pay that the patient can't afford. Another issue is the degree of sleep apnea that will trigger insurance reimbursement; mild cases are often not covered. It is also true that some HMO insurance plans will (perversely) pay for a sleep study but not pay for "durable medical equipment," so that the patient is not reimbursed for the machine. Finally, of course, millions of people have no insurance coverage, yet would greatly benefit from CPAP.

In any case, the huge volume of CPAP now in use in the U.S., and the fairly wide insurance coverage, has led to a viable business. Many companies now market CPAP machines. This competition breeds product improvement and better service, all to the patient's benefit. It is now fairly routine for CPAP apparatus to be delivered to the patient's home, and fully set up with hands-on instructions, all within 24 hours of a physician's order.

There is no doubt that nasal CPAP is the "gold standard" for treating obstructive sleep apnea. But to be effective it must be used for most of the night, and every night (or, for shift workers with sleep apnea, whatever part of the day they sleep). According to the ACCP consensus statement, adequate use of CPAP is defined as greater than 4.5 hours per night on a routine basis.

Perhaps 50% of patients quit using CPAP within the first year. The main reasons are inconvenience and discomfort. Most of these problems are solvable by finding a mask that fits properly, a machine with acceptable noise level, and (not least) a patient's understanding of the sleep problem.

Principal advantages of CPAP, besides its benefit for OSA, are that it can give immediate relief, is painless, and can be stopped instantly if not tolerated. This is in contrast to surgery, which is invariably painful, and can't be reversed if the procedure is ineffective.

There are many makes and models of CPAP machines. They are priced from a few hundred dollars to over $2000. The fancier models come with many bells and whistles, and as a rule are quieter than cheaper models.

In the last few years machines have been introduced that can determine the optimum pressure for the patient. These so-called 'auto-CPAP' machines HAVE NOT gained wide acceptance, for several reasons. One reason is that no study has shown them to be more effective than using a set pressure throughout the night. Also, these machines are much more expensive than conventional (fixed pressure) devices. Until there are studies proving the clear superiority of auto CPAP over fixe CPAP machines, the latter will continue to dominate the CPAP market.

The CPAP mask is a critical part of the CPAP treatment. Masks can cost anywhere from $100 to $200 depending on the make and model. If you cannot get comfortable with the mask or the mask does not fit properly, you will not be able to obtain the full benefits of CPAP. The standard CPAP mask is made of silicone and forms a seal over the nose. Some patients find the newer gel-filled masks more comfortable and obtain a better seal with them. Other patients feel too claustrophobic with their nose covered and prefer the "nasal pillows" which has 2 silicone fittings that go directly into the nostrils. The oils in the face will break the silicone down after 6 - 8 months, and the mask must then be replaced. Gel-filled masks tend to be more durable. Newer designs may incorporate features that allow you to replace only the worn out parts.

Problems with CPAP are mainly from intolerance (a feeling of claustrophobia is common). Other problems are facial pressure soreness from too tight a fit, noise (mainly from older, cheaper machines), dryness of mouth and throat (often alleviated with humidity which can be added to the circuit), and, rarely, nasal bleeding and sinus infection.

The three biggest obstacles to effective CPAP are:

Another important aspect of CPAP therapy is the supplier, i.e., the company that delives the CPAP machine and mask, sets it up in the home, instructs the patient on proper use, and then responds to any problems that may arise. The major equipment problem most patients encounter is the CPAP mask. The mask is like a new pair of shoes; the first pair you try on (or the 2nd or 3rd) may not fit. The patient should be prepared to change the mask, or the strap arrangement (or even the machine if it is too noisy or has some malfunction). The company has to serve the patient. Most companies do this well, but some patients have quit using CPAP because of poor company response to their complaints.

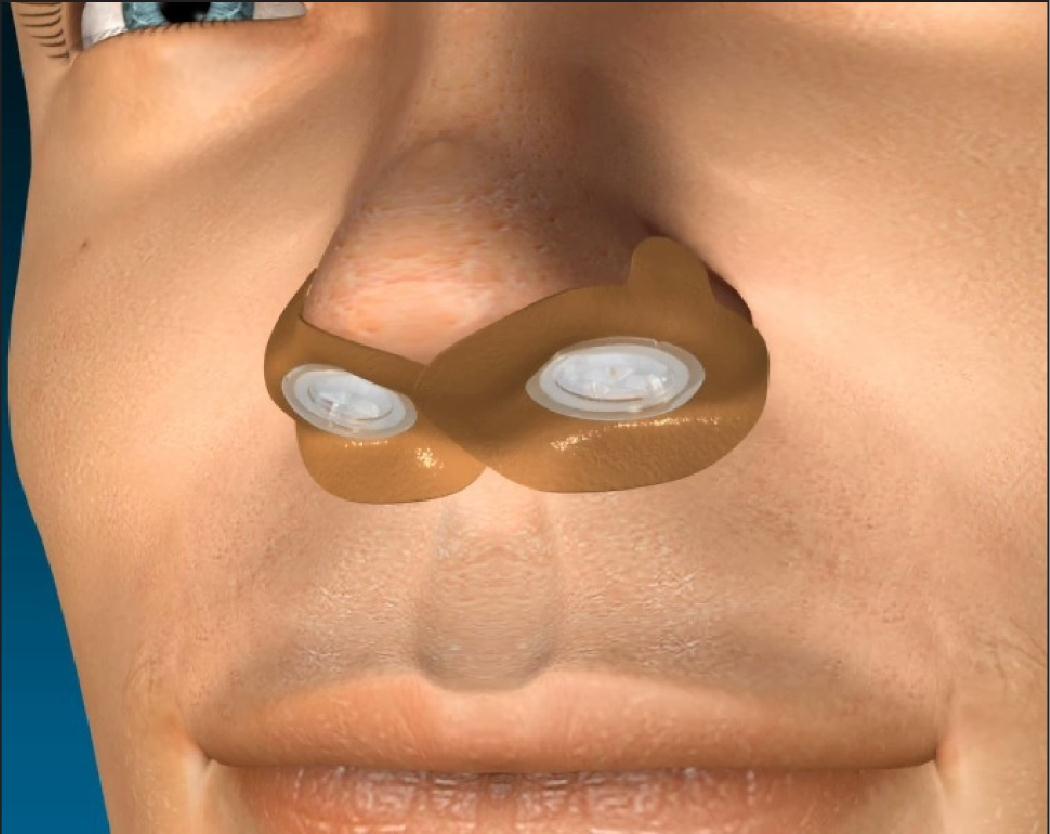

Provent

SUMMARY: As of mid-2011, Provent

is a relatively new FDA approved proprietary device for treating

obstructive sleep apnea. It is a 'one-way valve' that is taped into the nostrils, so that

the seal is airtight; being airtight, the patient cannot breathe around it, only through the openings.

Provent device securely fastened in patient's nostrils

Each nasal opening lets air in easily but then retards the flow of air coming out. Technically, airway resistance is very low going into the nose, very high exiting the nose. By increasing airway resistance on exhaling, the air pressure backs up in the throat and helps 'stent open' the airway, to keep it from collapsing. This is the same principle used in CPAP, which creates an increased pressure to keep the (otherwise collapsing) airway open.

Does it work? In one large, controlled study published in the journal Sleep, about 250 patients were divided into a treatment group and a 'sham group'. The treatment group got the Provent device, which they used nightly. The sham group used something that looks just like Provent, but it did not offer any resistance on breathing out. The results? Sleep apnea was signficantly improved with Provent, but not with the sham device. Also, the amount of daytime sleepiness in the treatment group was much better compared to the sham group.

Advantages of Provent include no tight-fitting mask or head straps required, no machine needed, and much easier portability. Disadvatages include the fact that it's not suitable for people who have low oxygen during sleep, and it's generally not as effective as CPAP. So in summary: not as good as CPAP, but much better than nothing. Expect more such devices to be developed and brought to market.

Surgery

SUMMARY: Surgery to the upper airway is a 'last resort' treatment for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. There are several surgical techniques; each carries risk of complications and may, despite considerable pain and discomfort, not be effective.

Surgery is by far the most complex therapy for snoring and OSA. One reason is the different procedures used by different surgeons. Surgeon A may recommend one procedure for your snoring, while Surgeon B will try a different approach. Ditto obstructive sleep apnea. Another reason is the simple fact that none of the commonly used techniques is more than 50% successful in the long run, and most are far below that. Finally, anything done surgically will be painful and expensive. No wonder most patients AND physicians are somewhat confused about the surgical approach to snoring and OSA. With this preamble, below is a table listing the principal techniques, their indication and drawbacks.

Surgical Techniques for Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

Operation |

Description of Surgery |

Perspective |

Result for snoring alone (without OSA) |

Result for OSA |

tracheostomy |

placing an opening in the trachea or wind pipe, effectively bypassing all upper airway obstruction |

done only for patients whose sleep apnea is considered life threatening; these patients usually have concomitant respiratory failure, i.e., failure to bring in oxygen even while awake. |

Never done for snoring alone |

Considered curative, since opening establishes an effective bypass for air to enter the lungs; however, rarely performed for OSA alone since it is considered a 'drastic' option. |

nasal surgery |

making the nasal air passages larger via traditional surgical techniques (e.g., fixing septal deviation), or newer methods such as laser or radiofrequency |

this surgery is commonly performed in patients with or without OSA who "can't breathe through my nose"; for patients with OSA, nasal surgery may help improve tolerance of the CPAP mask |

Since blocked nasal passages is rarely the sole cause of snoring or OSA, nasal surgery is not expected to cure either condition. |

Not helpful, except in faciliating use of CPAP mask when nasal passages are blocked |

genioglossal advancement, with hyoid myotomy and suspension (GAHM) |

'Facial reconstruction surgery': essentially moving the tongue forward to open up the back of the throat |

Operation performed only in highly selected cases: people with large tongues that tend to fall back and block the throat. Specific technique will vary with surgeon and patient's anatomy. Under general anesthesia; can be associated with major morbidity. |

Not for snoring alone |

Uncommon therapy for OSA; can be effective in selected cases |

maxillomandibular osteotomy and advancement |

'Facial reconstruction surgery': Essentially re-aligning the jaw by moving both the upper and lower jaws forward, maintaining dental occlusion; the result is that the tongue is advanced forward, opening up the back of the throat (the "retropalatal airway") |

Operation performed only in highly selected cases. Specific technique will vary with surgeon and patient's anatomy. Under general anesthesia; can be associated with major morbidity. |

Not for snoring alone |

Uncommon therapy for OSA; can be effective in selected cases |

UVVP (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty) |

Using a scalpel to remove part of the soft palate, and the uvula, to open up the back of the throat; tonsils are also removed if no prior tonsillectomy |

The 'traditional' surgery for OSA, UVVP is a major operation performed by ENT surgeon, under general anesthesia. There is significant post-operative pain. Specific technique will vary with surgeon and patient's anatomy. UVVP is now a second option, for patient's who can't tolerate CPAP or in whom CPAP has failed to correct OSA |

Up to 80% have immediate improvement, but snoring recurs in half of these patients |

Analysis of the uvulopalatopharyngoplasty papers revealed

that procedure is, at best, effective in treating less than

50% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. The site of

pharyngeal narrowing or collapse, although

identified by different and unvalidated methods, has a

marked effect on the probability of success of

uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. |

LAUP (laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty) |

using a laser to remove part of the soft palate and sometimes part of the back of the tongue, to open up the back of the throat; tonsils also removed if no prior tonsillectomy. Specific technique will vary with surgeon and patient's anatomy. |

Outpatient procedure. Doesn't require general anesthesia, but is painful once local anesthetic wears off; also, more than half of patients require multiple procedures (and hence is expensive long term) |

Not effective; can actually worsen OSA in some patients |

Up to 50% effective, after multiple procedures |

RFTVR (radio frequency tissue volume reduction); also known by trade name Somnoplasty |

essentially heat treatment to soft palate and base of tongue, to accomplish the same objectives as UVVP and LAUP. Tiny radiofrequency electrodes are inserted into soft palate and back of tongue. Low level radiofrequency energy generates heat, without burning, at temperatures between 167 andf 185 degrees F. This heat creates tiny lesions which then coagulate, and over time (several weeks) are absorbed. The aim is to reduce the volume of tissue and open up the airway. Specific technique will vary with surgeon and patient's anatomy. |

Office procedure under local anesthesia, approximately 30-45 minutes. Little pain, but Somnoplasty usually requires more than one procedure to be effective |

Effectiveness increases with multiple procedures, up to 61% effective (Ferguson M, Smith TL, Zanation AM, Yarbrough WG. Radiofrequency tissue volume reduction: multilesion vs. single lesion treatments for snoring. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:1113-18.) |

Effective in some cases of OSA |

Sclerotherapy |

injecting a sclerosing agent into soft palate, to 'scar down' the tissue; sodium tetradecyl sulfate is used (same agent use to sclerose varicose leg veins |

92% effective if snoring is generated from soft palate; not effective if snoring generated from base of tongue (Ferguson M, Smith TL, Zanation AM, Yarbrough WG. Radiofrequency tissue volume reduction: multilesion vs. single lesion treatments for snoring. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:1113-18.) |

Not tested; may be effective for mild OSA |

Office procedure, under local anesthesia - also 'low tech' and so less expensive than laser and radiofrequency procedures |

Sleep Home Page /

Internet Sleep Links /

Books about sleep

disorders (with links to Amazon.com) /

Drugs for Sleep & Awake /

Index of Dr. Martin's web sites

Forward any comments to: larry.martin@roadrunner.com