"Doctor, my husband stops breathing during sleep."

Clinical Professor of Medicine

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland

Board Certified in Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine

Sleep Home Page / Internet Sleep Links / Books about sleep disorders (with links to Amazon.com) / Drugs for Sleep & Awake / Index of Dr. Martin's web sites

|

Living is a disease from which sleep gives us relief eight hours a day.

Death, so called, is a thing which makes men weep: And yet a third of Life

is passed in sleep.

No small art is it to sleep: it is necessary for that purpose to keep awake all day.

Even where sleep is concerned, too much is a bad thing.

And if tonight my soul may find her peace in sleep, and sink in good oblivion,

and in the morning wake like a new-opened flower then I have

been dipped again in God, and new-created.

All men whilst they are awake are in one common world: but each of them, when he is

asleep, is in a world of his own.

Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care

|

Diagnosis

[Note: Names and some features of the patient have been changed to protect identity. None of the information in this story should be construed as specific medical advice for any individual. Anyone concerned about excessive sleepiness or abnormal sleep should consult his/her physician.]

September 4

Horace Wagner's problem is apparent in the first few minutes of his first visit. Not from any special clinical skill on my part, but because he shows up with his wife. In fact she made the appointment, and came along to provide the medical history.

He is 45, stands 5' 9" and weighs 290 lbs. He wears a large pullover shirt, with open collar to accommodate his 19" diameter neck. Billowy flesh hangs over a hidden Adam's apple. A huge belly bulges underneath the pullover. His face is round, clean shaven, with bright blue eyes and red cheeks, just the hint of middle age. His handshake is firm and he doesn't seem the least bit tired.

He is dressed casually, with shirt half out of the waist, as if he has just come from a round of golf. Mrs. Wagner, three years younger, is better dressed, in a grey business suit, appropriate for a job interview. She has a pretty, thin face with short black hair, average height and perhaps half her husband's weight. She holds an envelope in her right hand.

The Wagners take a seat in the office, and I pick up the intake sheet left by my nurse. It lists only a chief complaint ("my sleep is bad") and his blood pressure, 140/95. His list of medications includes two pills for high blood pressure and one for gout. Facing the patient I ask, "What seems to be the problem?" Mr. Wagner glances toward his wife, who speaks first.

"As I explained to your nurse, my husband stops breathing during sleep."

I write: 'Wife here w/ pt. - says he stops brth. dur. slp.'

"What do you mean, Mrs. Wagner? Can you describe what happens?"

"Yes. He snores heavily, he's been doing that for years. But lately when he snores, all of a sudden he'll stop sometimes. I mean he stops snoring, stops breathing. I don't hear anything. Then after a while he will jerk and snort, then start breathing again."

'Snores heavy, for yrs.; she notices apnea spells.'

This is about as classic a history for sleep apnea as a doctor can hope for. Diagnosis made, thank you m'am. Well, not exactly; I still have far to go. He stops breathing during sleep, but just how bad is it? And I haven't even heard Mr. Wagner speak. Turning to address him directly, I ask

"Do you know any of this is going on?"

In a soft voice, as if to minimize his weight, Mr. Wagner says "no, not really. She tells me about it in the morning." He does not seem particularly concerned. She is obviously more worried than her husband.

Husb. unaware of spells.

Back to her: "How long did you say this has been going on?" She opens the envelope and hands me a piece of paper, a hand written account of her observations, over a week's period, of his sleeping habits. "About a year," she says. "That's one week" she says, pointing to the paper in my hand. I briefly peruse her journal.

'Monday nite - snored heavy. Interrupted with no breathing at least 3 times before I fell asleep. 4 a.m. - he went to bathroom, I looked at clock. Waited from him to come back. More snoring. I fell asleep.'

'Tuesday nite - Stayed up while he went to sleep, 10:15 p.m.. Snoring, then held his breath 10:35 p.m. I punched him and he woke, briefly. Then back to sleep and snoring...'

Looking up from the paper I ask, "How long does he stop breathing for?"

"I don't know, sometimes it seems like a whole minute, sometimes just a few seconds. I get scared and shake him, and he starts breathing again. I can't be up with him all night." She is the one asking for help, but I need more info from him.

"Mr. Wagner, do you fall asleep during the day?" This is a rather open ended question, but a necessary one when evaluating potential sleep apnea. Everyone falls asleep during the day on occasion. But people who don't get a good night's sleep -- particularly when it is interrupted by repeated episodes of breathing cessation -- often fall asleep at the wrong times, or have a powerful urge to do so. Like while driving, operating machinery, talking to a customer, talking to the boss.

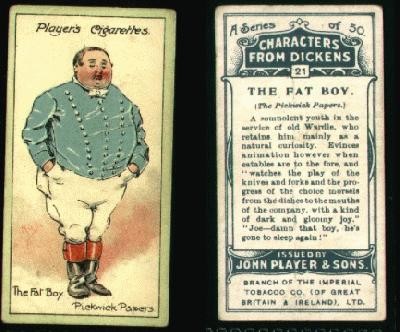

The classic, oft-quoted literary example of daytime sleepiness is from Charles Dickens' first novel, Pickwick Papers (1837). In Chapter 53 Dickens introduces the fat boy Joe (illustration from old cigarette package):

from Chapter 53, Pickwick papers

...A most violent and startling knocking was heard

at the door; it was not an ordinary double knock, but a constant and uninterrupted

succession of the loudest single raps, as if the knocker were endowed

with the perpetual motion, or the person outside had forgotten to leave

off. . .

The object that presented itself to the eyes

of the astonished clerk,

was a boy - a wonderfully fat boy - habited as a serving lad, standing

upright on the mat, with his eyes closed as if in sleep. He had never

seen such a fat boy, in or out of a travelling caravan; and this, coupled

with the calmness and repose of his appearance, so very different from

what was reasonably to have been expected in the inflicter of such

knock, smote him with wonder.

"What's the matter" inquired the clerk.

The

extraordinary boy replied not a word; but he nodded once, and

seemed, to the clerk's imagination, to snore feebly.

"Where do you come from?" inquired the clerk.

The boy made no sign. He breathed heavily,

but in all other respects was motionless. The clerk repeated the question thrice,

and receiving no answer, prepared to shut the door, when the boy suddenly opened his

eyes, winked several times, sneezed once, and raised his hand as if to

repeat the knocking. Finding the door open, he stared about him with

astonishment, and at length fixed his eyes on Mr. Lowten's face.

"What the devil do you knock in that way for?"

inquired the clerk, angrily.

"Which way?" said the boy, in a slow and sleepy

voice.

"Why, like forty hackney-coachmen," replied the clerk.

"Because master said, I wasn't to leave off

knocking till they opened the door, for fear I should go to sleep," said the boy.

Joe has daytime hypersomnolence -- extreme sleepiness -- and so does Mr.

Wagner. Over the next few minutes I learn he is a short haul truck driver, that he

was ticketed once, about a year earlier, after falling asleep at the wheel and hitting

a parked car. No one was injured. He now routinely drinks "a ton of coffee" to

stay awake, and will pull over if he feels sleepy, which is fairly often. He has

turned down inter-city driving jobs because he fears falling asleep on the highway.

"Then why didn't you come earlier to see someone?

Why did you wait on

your wife to make the appointment?" There is no answer. He just shrugs his

shoulders.

* * *

Mr. Wagner is obese, has daytime somnolence,

and his wife says he stops breathing during sleep: the classic signs and symptoms of

obstructive sleep apnea. I know what to do next: finish my evaluation with a physical

exam and review of his medical history; arrange for an overnight sleep study to confirm the

diagnosis and its severity; start treatment. But for the moment I am somewhat

turned off by his insouciance, by what I perceive to be a less-than-appropriate

concern for his serious health problem. I fantasize jumping up, Bulworth-like,

and rapping:

Listennuppp!

You're too fat, too much bread.

Your wife's afraid you'll soon drop dead.

Cause in your sleep, she does perceive,

That when you doze you do not breathe.

* * *

Go to the search engine google.com

and type in "sleep apnea." You will

retrieve (in less than a second) over 3 million web sites. It is a mind boggling list,

especially for a diagnosis that was infrequently made (and less frequently

treated) a mere 20 years ago. In the pantheon of medicine the

history of sleep research is relatively brief. It was not until the

1950s and 1960s that scientists characterized the major stages of sleep.

These are the 4 normal sleep stages we go through in a given night,

from Stages 1 or 'light sleep' to Stage 2 where we spend the majority of sleep

and then to Stage 3, or "deep sleep" where arousal from sleep is the most

difficult. Then there is altogether different stage called REM, for the rapid eye movements that occur in this

stage. REM is so characteristically different from the rest of sleep that

the other 3 stages are called 'non-REM' sleep, or 'NREM' for short.

The sleep stages are largely characterized by variations in brain wave

patterns, electrical activity picked up by electrodes attached to the skull;

the recorded brain wave patterns are called

electroencephalogram or EEG. (Not to be confused with EKG, which measures

electrical activity of the heart.)

The EEG is one component of the overnight sleep study, called

polysomnography

(poly - many; somnogram - recordings

during sleep). Here is a classification of the four sleep stages.

NREM (non-rapid eye movement) sleep

Body is relatively active but there is a dearth of mental activity,

little if any dreaming. NREM has 3 distinct stages.

Stage 1 - First and lightest stage; easiest to arouse from; occupies about

15% of total sleep time.

Stage 2 - Next lightest stage; somewhat harder to arouse from; occupies

about 50% of normal sleep time.

Stages 3 (combines 3 & 4) - In 2007 a change in nomenclature combined what used to be called

stages 3 & 4 into a single stage 3. In stage 3 the brain waves are much slower in

frequency than Stages 1 and 2. Stage 3 (or stages 3 and 4 in the older

nomenclature) is "deep sleep," and occupies about 10% of total sleep time.

REM (rapid eye movement) sleep

REM usually begins between 60 and 90

minutes after first falling sleep, then reappears two or three more times throughout

the night.

REM occupies about 20-25% of sleep time. During REM the body is relatively immobile, with little muscle

movement, but the brain is very active. REM is where most dreams occur.

A typical night's normal sleep pattern is shown below in the graphic form

of a hypnogram. Below the hypnogram is a listing of each stage with the

times they begin. Note that the new standard nomenclature combines stages

3 and 4 into a single stage 3. Stages 1 and 2 are generally light or

lighter sleep, and 3 and 4 are generally deep or deeper sleep. Together,

1, 2 & 3 (or 1, 2, 3 & 4) is called 'Non-REM' sleep to distinguish it from REM

sleep, which is altogether different. REM sleep is where most dreaming

occurs.

Times refer to the hypnogram above.

10:15 p.m. Lights out

10:30 p.m. Onset Stage 1 - sleep

begins

10:35 p.m. Stage 2

10:50 p.m. Stage 3

11:00 p.m. Stage 4 ('A',

'B' and 'C' label occurrences of stage 4 or deep sleep; note that in the new

nomenclature stages 3 & 4 are now combined as Stage 3.)

11:45 p.m. Stage 3

11:55 a.m. REM

00:15 a.m. Stage 1

00:25 a.m. Stage 2

00:30 a.m. Stage 4

1:05 a.m. Stage 1

1:15 a.m. Awake, eyes closed

1:18 a.m. Stage 1

1:30 a.m. REM

1:50 a.m. Stage 1

2:00 a.m. Awake, eyes closed

2:04 a.m. Stage 1

2:12 a.m. Stage 1

2:30 a.m. Stage 3

2:45 a.m. Stage 1

3:15 a.m. REM

3:45 a.m. Stage 1

3:50 a.m. Awake, eyes close

3:58 a.m. Stage 2

5:05 a.m. REM

6:10 a.m. Awake, eyes close

6:45 a.m. Awake, eyes open & recording ends

Notwithstanding all the literary attention paid to sleep over the centuries, medical science was largely ignorant of what Shakespeare called the "chief nourisher in life's feast" until the last few decades. After scientific nosology of normal sleep was worked out in the 1950s and 1960s, the field of EM>sleep disorders grew rapidly. However, it is only in the last two decades that the field broadened from the exclusive province of academic medical centers into the offices of practicing physicians. During that period four developments coalesced to catapult sleep disorders into mainstream medicine:

- a collection of scientific studies, from around the world, demonstrating that sleep disorders are, in fact, fairly common, and that there are effective remedies for some of them;

- affordable PC-based technology to monitor and record the myriad physiologic changes during sleep;

- reimbursement by insurers for performing and interpreting a patient's sleep study.

- adoption of sleep medicine as an area of interest by various medical professionals (particularly in fields of neurology, pulmonary diseases and psychiatry), along with training of many technicians to help administer the studies.

These four developments laid the foundations for a new medical field: scientific publications, to show its validity; affordable technology, to record the data; a cadre of professionals, to diagnose and treat the patients. Phoenix-like, the field of 'sleep disorders' has grown to occupy center stage in American medicine. In 1996 the American Medical Association recognized sleep medicine as a new specialty. Today there are sleep medical journals, sleep medicine symposia, specialists who do nothing but sleep medicine, and many equipment companies to service the market. There are also numerous consumer-oriented books for people who suffer sleep disorders. The field is big and getting bigger.

Many individual sleep disorders have their own non-profit organizations designed to promote research and education. One example is The American Sleep Apnea Association. Sleep is not only mainstream in professional circles, but also in the lay consciousness. Sleep disorders are discussed, promoted, written about practically everywhere - magazines, television, and of course the internet. Think millions of web sites. The mantra is by now familiar:

|

One third of our lives is spent asleep. How we sleep affects how we feel during the day. Many things can prevent a good night's sleep. Sleep apnea is common, affecting 4-6% of all middle aged men, and many women, too. It is associated with high blood pressure, excessive daytime sleepiness, stroke and heart disease. If doctors can diagnose the sleep disorder and treat it, the patient [implied to be you or your loved one] will greatly benefit.... |

Sleep apnea is the most common serious sleep disorder, but there are many others. In The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd Edition, a 380-page manual published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, adult obstructive sleep apnea occupies just 10 pages. But the ICSD lists everything sleep-related, from nightmare disorder (6 pages) to sleep bruxism (grinding your teeth during sleep; 9 pages).

Snoring is the most common sleep complaint; while often a herald of the sleep apnea syndrome, snoring is several fold more common than the syndrome and is little more than in annoyance for most people. Particular in obese men and women, though, excessive snoring should trigger a sleep study to see if there is also apnea.

Insomnia is also common, and very resistant to treatment, usually requiring behavioral modification. Early morning awakening is a well known symptom among depressives, and a reason for lack of sleep unrelated to apnea. Restless legs syndrome is a peculiar malady sometimes associated with involuntary limb movement during sleep. In severe cases, limb movement is associated with a lighter sleep stage (called an 'arousal', referring to brain wave activity and nothing sexual); the result can be a night of inadequate sleep.

Narcolepsy is often confused with ordinary daytime sleepiness. The former is a pathologic state characterized by "sleep attacks", altogether different from the latter. Narcolepsy can be diagnosed by specific brain wave and muscle activity in a specialized daytime study called multiple sleep latency test. Sleep walking and recurrent nightmares are other conditions plaguing some people. And then there is sleep paralysis, where the body is literally paralyzed for a brief but frightening interval.

In thinking of sleep as a field of human study, nutrition provides an interesting parallel. Sleep and daytime sleepiness are like nutrition and weight control. Sleep and food are both vital, in the literal meaning of the word unlike, say, sex, which is not (literally) vital because you won't die without it. You eat and sleep because you have to. Every sentient being has an interest in food and sleep, and perhaps a personal anecdote or two, but very few people understand what they are all about (What happens to food when you eat it? What happens when you fall asleep?).

You can voluntarily screw up your diet and get sick, or sickness can mess up your eating habits. You can voluntarily screw up your sleep (late to bed early to rise) and get sick, or sickness (depression, obesity) can mess up your sleeping habits.

As with the study of food (nutrition), the study of sleep cuts across many professional lines. Physicians with a direct, professional interest include lung doctors, ear nose and throat doctors, oral surgeons, psychiatrists, pediatricians, and neurologists.

If medicine is big business, sleep is a major sideline, and growing. And like any endeavor where there is profit to be made, sleep has generated competition: between hospitals and sleep labs for patients, and between companies that market the necessary equipment. Many hospitals now boast a sleep lab where patients (usually 1 to 3 per night) come to sleep in specially-equipped rooms where they are monitored throughout the night. Each patient is a potential 'money maker' for the hospital, and a source of revenue for physicians who interpret the studies.

This entrepreneurship is not a bad situation. The profit potential has increased awareness of sleep disorders, raised sleep lab standards, and helped motivate physicians to become expert in the area. The result: better diagnosis, better treatment.

* * *

Mr. Wagner's medical evaluation (the 'work up') is relatively straightforward, and a good example of most cases are evaluated.

|

1. SUSPECT DIAGNOSIS. Suspicion can come from a bed partner, or from the patient himself if he or she notices abnormal sleep patterns or excessive daytime sleepiness. Physician consulted. 2. OBTAIN DETAILED HISTORY. Physician looks for one or more of three important characteristics: -> history of stopping breathing during sleep, typically related by a bed partner; -> excessive snoring, particularly if associated with obesity; --> daytime hypersomnolence, or excessive daytime fatigue not otherwise explained. Daytime hypersomnolence is usefully assessed by the self-administered Epworth Sleepiness Scale (see below). Though OSA is more common in the morbidly obese, it can also occur in normal weight individuals. Thus any one of the three characteristics listed above will suffice to order a sleep study. 3. ARRANGE FOR SLEEP STUDY (the polysomnogram). The test is usually done in a specially-equipped sleep lab, either in the hospital or a free-standing sleep center. However, in some situations a polysomnogram can also be done in the patient's home. 4. INTERPRET POLYSOMNOGRAM. Report is sent to whoever ordered the test, as well as to the primary care physician if different. 5. RECOMMEND THERAPY. |

At some point in the evaluation process, the subject will be asked to fill out a simple questionnaire called the "Epworth Sleepiness Scale". This is a series of simple questions to gauge 'how bad is your daytime sleepiness?', and is used by sleep labs all over the world. The Scale is named after the Epworth Hospital Sleep Disorders Unit in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, where it was developed.

|

THE EPWORTH SLEEPINESS SCALE

How likely are you to doze off or fall asleep in the following situations, in contrast to feeling just tired? This refers to your usual way of life in recent times. Even if you have not done some of these things recently try to work out how they would have affected you. Use the following scale to choose the most appropriate number for each situation: 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing SITUATION --- CHANCE OF DOZING Sitting and reading --- 0-1-2-3 Watching TV --- 0-1-2-3 Sitting inactive in a public place (e.g, a theater or a meeting) --- 0-1-2-3 As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break --- 0-1-2-3 Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit --- 0-1-2-3 Sitting and talking to someone --- 0-1-2-3 Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol --- 0-1-2-3 In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic --- 0-1-2-3 Check your total score to see how sleepy you are. A score of 10 or higher is considered the threshold of "excessive daytime sleepiness". |

Mr. Wagner agrees to take the test home with him, and hands it in at the time of his sleep study. His score is 17.

Treatment

A paradox of sleep studies is this: the patient we send for the study likely has abnormal sleep of some sort. The overnight sleep study is to find out what kind of abnormality, and how severe. But then we place the patient into an alien, wired environment, unlike any he/she ever sleeps in. How can you test for a sleep abnormality when the test environment is itself not normal?

The room is clean, has a twin or queen-sized bed, and is dark with the lights out. These rooms are either in hotels or, if in medical buildings, are decorated like a motel/hotel room. But still, the room is not the patient's native environment. Home certainly doesn't come with monitoring wires, a wide angle video camera aimed at the bed, and technicians with computers who monitor every movement and breath. As for the wires, they lead from sophisticated measuring devices to the patient's anatomy - scalp, eye lids, nose, chest, legs.

Perhaps the surprising thing is that, most of the time, the artificial environment doesn't matter. A bed is a bed, and for most patients with a chronic sleep problem, especially if severe, the study will reveal the problem. But the single night study that most patients have is only a 'snapshot' of sleep, and sometimes can be inconclusive or equivocal. If time and money were not limiting factors, many patients would certainly benefit by having more than one study, to establish a clear pattern of abnormality.

(The current situation is somewhat analogous to taking a patient's blood pressure once, then embarking on long term therapy based on that single measurement. Of course blood pressure measurement is a simple and inexpensive test, the antithesis of a formal sleep study. No doubt there will come a time when sleep studies can be done without all the wires, and in the comfort of the subject's own bedroom. Then physicians can collate results from several nights, and arrive at a more accurate picture of sleep abnormalities. For now, though, we are generally relegated to a single night of data in a somewhat artificial environment, after which me must decide to treat or not treat the patient.)

* * *

Three weeks have passed and Mr. Wagner has had his sleep study. It confirms the diagnosis, in spades. Over 50 times each hour part of his upper airway -- the area just behind and below the base of the tongue -- shuts down partly or completely. And with each closure or partial closure his blood oxygen level falls.

From an engineering standpoint, design of the respiratory system is flawed because the upper airway is not redundant. We can breathe air through our nose or mouth, either portal being sufficient to inhale all the air we need. But after air from the nose and mouth meet in the back of the throat, it travels down a single upper airway into our two lungs (the "lower" airways).

Either of our two lungs is sufficient to sustain life (as patients who have lost one to surgery can attest). But the upper airway is a single tube. Partial or intermittent obstruction can give all sorts of problems --shortness of breath, cough, low blood oxygen level, sleep deprivation. Complete obstruction will cause death within minutes. There is no alternative route for air to enter our lungs.

The upper airway is not a uniform tube but instead is a series of different structures (the pharynx, the larynx, the trachea) whose only common feature is that air goes through them on its way to the lungs. There are many ways these upper airway structures can obstruct. The most common, perhaps, occurs during sleep -- and leads to obstructive sleep apnea. The muscles just below the back of the throat relax during sleep, and/or the tongue falls back into the throat, and as a result the upper airway narrows or fully obstructs. Airflow slows severely or stops completely - apnea. Excess fat in the upper airway makes this problem worse, which is why sleep apnea is so much more common in obesity (a fat neck means fat is inside the throat also).

So why don't people like Mr. Wagner die? Likely some people with undiagnosed sleep apnea do die during sleep, because each time the air supply is cut off the oxygen level falls. If there is underlying vascular disease, it is not a stretch to envision a fatal heart attack or stroke from the low oxygen supply. Surprisingly, we don't know how often this occurs from sleep apnea, but certainly there must be increased risk in these patients.

However Mt. Wagner, like the vast majority of patients with obstructive sleep apnea, doesn't die because each time the upper airway obstructs his brain wakes up a little. He repeatedly has abrupt changes from a REM or a deeper stage of NREM sleep (Stage 3-4) to a lighter one (Stage 2 or 1), or from Stage 1 or 2 to a brief awakening. In the parlance of sleep lingo, these frequent transitions are called arousals. With each arousal his muscle tone increases, and the upper airway blockage opens up. (As Mrs. Wagner noted: "Then after a while he will jerk and snort, then start breathing again.")

But 50 times an hour! Instead of a night spent mostly in deep sleep, his night is spent mostly in light sleep. He has slept without really sleeping. In the morning, on awakening, he is tired and exhausted. Sleep apnea has robbed him of a good night's sleep. And this has been going on a long time.

Of course I am not present at the sleep study. Physicians have to rely on sleep lab technicians to monitor their patients and to provide therapy when needed. In fact, a well run lab is equipped to both diagnose the problem and begin treatment the same night.

Treatment is a mask placed snugly over the nose, and attached to a machine to push air down the throat. That's a lot of treatment. We're not talking a pill or anything like that. There is in fact no pill, no medication, for obstructive sleep apnea. We're talking about a stream of air pushed down the throat during each breath, so that the upper airway stays open all during sleep.

Imagine a collapsible rubber tube about 6 inches long. Blow through the tube and it stays open. Stop blowing and it collapses. A very simple principle. To work in humans, the machine must deliver a positive pressure to the upper airway on each inspiration. For comfort and convenience the nose has become the favored portal of entry (over the mouth, or mouth and nose together). So the mask fits snugly over the nose (held in place by straps) and air is forced through the nasal passages continuously every time the subject takes in a breath. The method is called CPAP - continuous positive airway pressure -- and it has revolutionized treatment of OSA.

Man with nasal CPAP mask. The mask is linked to a CPAP machine that delivers a pressurized breath every time he inhales. This pressurized prevents the airway from collapsing on exhalation.

CPAP works. Dramatically so. If the patient can get past the early discomfort of the CPAP mask and can tolerate the slight whooshing sound of the machine, he or she will usually get a good night's sleep and, often, feel like a new person. No more daytime somnolence, no more excessive fatigue. Even blood pressure will improve in many patients. And certainly the risk of sudden death -- not known with certainty but likely higher than in people without sleep apnea -- will decrease.

|

You Tube Videos on Sleep Apnea and CPAP

Rosie O'Donnell & CPAP - from "The View" |

Three hours into Mr. Wagner's sleep study, the lab technician wakes him up because of excessive episodes of airway obstruction, and fits him with a CPAP mask. (The possibility of starting CPAP in the middle of the study had been explained to Mr. Wagner before he went to sleep). He spends the rest of the night with the mask, while the tech adjusts the pressure settings. The results are dramatic.

A few days later I interpret his sleep study, and finish my two page report with the following summary (quoted verbatim, with explanations in brackets).

|

THE MT. SINAI MEDICAL CENTER POLYSOMNOGRAPHIC REPORT

Name: Horace Wagner

Record No: 894501

Age: 45

Date of Study: September 14, 20xx

SUMMARY

|

| Lawrence Martin, MD |

* * *

A week after the study the Wagners are back

in the office.

"How'd it go?" meaning the sleep study on

September 14.

"OK. They kept fiddling with the mask."

"You know, it helped you quite a bit.

Your airway obstruction was reversed. You had a great result. Do you think you would use it at home?"

"I suppose so." He is frustratingly non-committal.

I go into lecture mode.

"Well, let me explain what we know so far.

You definitely have what your

wife has suspected, which is obstructive sleep apnea. Your airway (I point to his neck)

closes off over 50 times an hour, and as a result your sleep is no good.

Every time your airway closes it gives a jolt to your brain so you'll open the

airway and let more oxygen in. As a result of all these closes and jolts

to your brain, your natural sleep is severely interrupted. That's why

you're so sleepy all the time. Even after you've slept -- sort of -- for 8

hours. It's just not good sleep.

"There are only three basic treatments for

this problem", I explain. "Actually," I hasten to add for completeness,"

there are probably a few more that have been tried, but only three are

realistic in his case." (Mrs. Wagner is silent, but hangs onto every word).

"The best treatment is weight loss, but

I know that's hard to do." (I am being

kind. Sufficient weight loss to reverse the apnea spells is practically impossible for

all patients, and the prudent physician never waits on this therapy before starting

CPAP.)

"If you could lose a hundred pounds, that would

likely do wonders for your sleep apnea.

But to do it safely would take a year or more, and without a

structured program it's unlikely to occur. Didn't you say you lost weight once?"

His wife speaks up. "Horace lost 50 lbs. with

a [protein sparing] diet some years ago, but he put it all back on." Mr. Wagner

nods his head in agreement with what his wife says. "The second - and probably the best - therapy

is that mask, what we call the

CPAP mask.

About two-thirds of patients we diagnose with sleep apnea use it,

and get a good result like you did, at least during the study.

But the other third can't use it, or won't. Mrs. Wagner,

have you had a chance to see the mask?"

"No, I haven't. But Horace told me about it."

"Well, it makes some a slight whooshing sound, but is much quieter than they

used to be. Almost always the spouse finds it more pleasant than the

snoring that it eliminates. Most important, it should really help your

husband.

"Oh, it won't bother me. I sleep with the TV on."

"You said there was a third option?" This from Mr. Wagner.

"Yes, the third option is

Sleep apnea surgery. An ENT [ear, nose, throat] surgeon

can clear out any excess tissue in the back of your throat, but we no longer

recommend it as a first treatment. Too often it just doesn't work, and the

surgery's painful to boot. Our won't even do it now CPAP is tried first. If you want to

consider surgery I can refer you to an ENT doctor, they're the ones who do the

surgery."

"No, no, I'm not ready for that now."

Just as well. I have truncated numerous articles and symposia on airway surgery

for OSA into just a few sentences. I have given him the essence of an evolving

field of OSA therapy, one that works for only a few select patients and does little

for the rest of them except cause pain and discomfort. Years ago surgeons

routinely operated

without a trial of CPAP, but that's not the case any more. CPAP is better,

if the patient can use it. And at least with CPAP nothing is lost if it doesn't work.

(For more detailed comparison of CPAP vs. Surgery for OSA, see

"I can't wear

that #!%{&!!# mask!".)

"Do you have any questions?"

They do, about insurance [if insurers pay for

the sleep study they usually pay for the

CPAP machine, which is set up by a medical equipment provider], follow up [with

me], option to go to surgery if CPAP isn't tolerated [yes], and diet help

[referral to dietician offered].

In the end, Mr. Wagner agrees to try CPAP at home.

I make the arrangements, and

schedule a follow up appointment in a month.

Follow up

October 21

It is just over a month since starting CPAP. He is in the office for a re-check, this time without Mrs. Wagner.

"How's it going? Are you using the machine?

"Yes, it's working pretty well."

"How many hours a night are you using it?"

"The whole night." I am somewhat skeptical of his quick answer. First, a large percentage of patients quit using it for a variety of reasons, and those that stay with CPAP rarely use it "the whole night." To be effective in relieving daytime symptoms, CPAP should be used at least 4-5 hours a night.

"It doesn't bother you?"

"No, I got used to it. And you're right, I do feel better during the day. A lot better. None of that sleepiness like I use to have."

"So you don't take it off until you get up in the morning?"

"Yeh. I was surprised, but I guess I'm sleeping the whole night."

"Wow, that's great. You're like a testimonial for CPAP. I sort of had a feeling you weren't going to even try it, let alone use it the whole night."

"No, I use it. My wife got used to it, so it's no problem. How long do you think I'll need this mask for?"

Good question. I look at today's weight. 290 lbs.

"I see you haven't lost any weight yet. Unless you lose the weight, probably indefinitely. There's also the surgical option we discussed, if you can't continue with the mask, but I don't recommend it."

"No, no, I'm going to lose the weight. We're going to meet with a dietician."

"OK. Well, I need to see you every few months for the first year, and we'll check on your progress. But if you have any questions you can call me anytime."

I note in his chart:

|

Dx: OSA, RDI initially 57 On CPAP 10 cm H20, tolerating well. Imprv. daytime Sxs [symptoms] RTN 3 months. L. Martin, M.D. |

- The End -

Read more on Sleep apnea from the NIH:

Signs of sleep apnea

Diagnosis of sleep apnea

Causes of sleep apnea

Treatment of sleep apnea

Sleep Home Page /

Internet Sleep Links /

Books about sleep

disorders (with links to Amazon.com) /

Drugs for Sleep & Awake /

Index of Dr. Martin's web sites

Forward any comments to:

drlarry437@gmail.com

Copyright © 2009-2014, Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Forward any comments to: drlarry437@gmail.com