We Can't Kill Your Mother! & Other Stories of Intensive Care. Medical and Ethical

|

What about spacers for metered dose inhalers?Spacers have long been used with pMDIs to make it easier for patients to inhale the medication. Another name for spacers is aerosol-holding chambers. Two examples are shown below: a rigid plastic spacer on the left and a collapsible spacer. The pMDI inserts in one part of the spacer and the patient inhales from a chamber that holds the medication. When the pMDI is compressed the medication aerosol enters the spacer and the patient can breathe normally via a mouthpiece without the need to closely coordinate inspiration with medication release. There are many different types of spacers available.

Pros: Spacers makes it easier to inhale the medication, helping assure that

it enters the lungs and not the room environment or just the back of the throat.

The Asthma Society of Canada recommends that anyone using a puffer consider

a spacer.

|

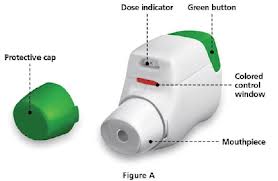

DRY POWDERED INHALERS (DPIs)

With DPIs the patient's breath (rather than hand action) actuates delivery of the

medication. You cannot see the spray because the only way to get the medication is to

inhale it from the mouthpiece. Within the DPI category, there are two broad types:

DPI Type 1): the medication is contained within the inhaler device at all times,

until inhaled, or

DPI Type 2): the medication comes in a separate capsule that must be placed

into the inhaler device at the time of use.

One study that received wide publicity showed that up to 1/3 of patients use

DPIs incorrectly. The error rate increased with patient's age, and

correlated with lack of instruction to the patient.

DPI Type 1. Medication is contained within the device

- Turbuhaler (also known as Flexhaler).

Several medications are delivered via the tubuhaler, including the steroid

Pulmicort

(shown below; the manufacturer, Astra Zeneca calls their device a "Flexhaler,"

just another name for turbuhaler). The turbuhaler requires you to

twist the dark cap shown at the bottom in order to activate the

next inhalation. The turbuhaler (flexhaler)

eliminates the type of coordinated effort needed for

traditional MDIs, since once activated all you have to do

is inhale from the mouthpiece. However, the bottom cap can twist

both right and left, and it's not obvious which

way activates the flexhaler. Thus some patients twist

it so as to close the chamber, preventing delivery

of medication when they inhale. For instructions on how to use

the turbuhaler/flexhaler, see:

National Jewish Hospitals web site

Asthma Society of Canada web site

DPI Type 1): the medication is contained within the inhaler device at all times,

until inhaled, or

DPI Type 2): the medication comes in a separate capsule that must be placed

into the inhaler device at the time of use.

DPI Type 1. Medication is contained within the device

- Turbuhaler (also known as Flexhaler).

Several medications are delivered via the tubuhaler, including the steroid

Pulmicort

(shown below; the manufacturer, Astra Zeneca calls their device a "Flexhaler,"

just another name for turbuhaler). The turbuhaler requires you to

twist the dark cap shown at the bottom in order to activate the

next inhalation. The turbuhaler (flexhaler)

eliminates the type of coordinated effort needed for

traditional MDIs, since once activated all you have to do

is inhale from the mouthpiece. However, the bottom cap can twist

both right and left, and it's not obvious which

way activates the flexhaler. Thus some patients twist

it so as to close the chamber, preventing delivery

of medication when they inhale. For instructions on how to use

the turbuhaler/flexhaler, see:

National Jewish Hospitals web site

Asthma Society of Canada web site

National Jewish Hospital web site

Asthma Society of Canada web site

Asthma Society of Canada web site

DPI Type 2. Medication is separate from the inhaler, in a capsule

- Handihaler (see below). The widely used drug

Spiriva

(tiotropium bromide) is delivered in this device. (Technically Spiriva

is for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, not asthma. However, many patients

with"asthma" also have chronic lung disease and are prescribed Spiriva.)

With the handihaler (as with the aerosolizer, below), the

actual medication resides apart from the device,

in capsules that are individually packaged.

The patient must: retrieve the capsule from its

wrapping, place it into the chamber of the handihaler,

close the chamber with a cap, then pierce the capsule by

pushing hard on a lever to the side of the handihaler. It's

a lot of steps! Furthermore, there are anecdotal reports of patients

who swallow the capsule instead of putting into the

chamber for puncture. The drug works well IF the patient is

instructed how to use the device and can perform the

required maneuvers. Without adequate instruction,

proper use is unlikely.For instructions on how to use the handihaler, see

National Jewish Hospital web site.

- Aerolizer. Like the handihaler (discussed above), the aerolizer consists of a plastic device to inhale medication. A capsule of powdered medication is placed in the device and its delivery is breath activated. Foradil, a long acting bronchodilator, comes in this device (shown below). For instructions on how to use the aerolizer, see National Jewish Hospital web site.

PROPELLANT-FREE "SOFT MIST" INHALERS

This is the latest type of inhaler for asthma and COPD. At this writing there is only one soft mist inhaler

marketed in the United States,

Combivent Respimat, shown in the photo.

Combivent has long been available in a

different format, with CFC (chlorofluorocarbon) propellant. The

Respimat device does away with the propellant and delivers

the drug as a fine mist. Why the change in delivery system?

According to the drug company's web site:

Combivent has long been available in a

different format, with CFC (chlorofluorocarbon) propellant. The

Respimat device does away with the propellant and delivers

the drug as a fine mist. Why the change in delivery system?

According to the drug company's web site:

Under the Clean Air Act, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has ordered products containing certain propellants, including COMBIVENT MDI, to be removed from the market. COMBIVENT RESPIMAT does not contain any of these harmful propellants and uses a spring mechanism to release the medication. Supplies of COMBIVENT MDI may run out in the second quarter of 2013. For more information on the Clean Air Act and CFCs, see this information from the Food and Drug Administration.

NOTE: Combivent is marketed for COPD, but many patients "with asthma" use it as well.

Unlike the FDA, physicians can't and don't strictly categorize patients with airway obstruction

into "COPD" and "asthma." In adult patients the conditions frequently overlap.

As to the Respimat delivery system, it is anticipated that other drugs will

soon be released using the device. As with ALL inhalers, its use is

not intuitive, and patients should be shown at least once how to use the device. This

can be done by the physician, nurse, medical assistant or pharmacist.

The company gives placebo devices to physicians for demonstration purposes.

NOTE: When these inhalers -- pMDIs, DPIs, Respimat "soft mist" -- are tested in drug

studies there is virtually unlimited support and follow up to assure

the study patients use them correctly. This support is funded

by the drug companies, who obviously want to know if the medication is

effective, so they spend whatever it takes to make sure the enrolled patients are

properly instructed and know how to use the inhalers. That level of education

and support for inhaler use is seldom available in clinical practice,

resulting in discrepancy between the effectiveness of the drug in

published studies vs. the real world. The medication itself may be good

but the delivery system is complicated and prone to mis-use; as a result,

improperly-used inhalers are often the 'weak link' in treating a patient's lung disease.

2. Thinking a written prescription for an asthma inhaler means the patient knows when to use it: The drug's purpose.

For treatment purposes all asthma inhalers fall into one of

two broad categories:

a) to provide quick relief ('rescue inhalers') and

b) to improve chronic symptoms and prevent flareups ('maintenance inhalers').

Examples of rescue inhalers are albuterol (brand names Proventil HFA,

ProAir HFA, Ventolin HFA). levalbuterol (brand name Xopenex), and ipratropium

bromide (brand name Atrovent). Combivent contains a combination of albuterol and ipratropium bromide. Although

Combivent is marketed (and FDA-approved) for COPD, in fact patients often use it as a rescue inhaler as well.

Maintenance inhalers include any inhaled steroid (IS),

either alone (brand names Azmacort, Qvar, Pulmicort, Flovent, etc.)

or in combination with a 'long acting bronchodilator' (LABD). Brand names of available combination IS-LABD products are:

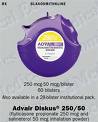

- Advair (GlaxoSmithKline) (fluticasone + salmeterol; DOSES: 100/50, 250/50 and 500/50; one puff twice a day)

- Symbicort (AstraZeneca) (budesonide + formoterol; DOSES: 80/4.5 and 150/4.5; 2 puffs twice a day)

- Dulera (Merck) (mometasone + formoterol; DOSES: 100/5 and 200/5, 2 puffs twice a day)

PROBLEM: The SAME type of delivery device (size, shape,

mechanism of action) is commonly used for both

rescue and maintenance inhalers. For example, as shown below,

ProAir HFA (a rescue inhaler, on left) and

Symbicort (a maintenance inhaler, on

right) both come packaged as pressurized metered dose inhalers, and

both are deep red in color. There is nothing intuitive about this.

For a patient who may have both inhalers (quite common), and who

becomes short of breath, it is all too easy to forget which is which.

- Advair (GlaxoSmithKline) (fluticasone + salmeterol; DOSES: 100/50, 250/50 and 500/50; one puff twice a day)

- Symbicort (AstraZeneca) (budesonide + formoterol; DOSES: 80/4.5 and 150/4.5; 2 puffs twice a day)

- Dulera (Merck) (mometasone + formoterol; DOSES: 100/5 and 200/5, 2 puffs twice a day)

PROBLEM: The SAME type of delivery device (size, shape,

mechanism of action) is commonly used for both

rescue and maintenance inhalers. For example, as shown below,

ProAir HFA (a rescue inhaler, on left) and

Symbicort (a maintenance inhaler, on

right) both come packaged as pressurized metered dose inhalers, and

both are deep red in color. There is nothing intuitive about this.

For a patient who may have both inhalers (quite common), and who

becomes short of breath, it is all too easy to forget which is which.

This confusing situation happens often, even when the rescue and maintenance inhalers are of different color. The root problem is lack of standardization among inhalers, with unclear labeling to distinguish between rescue and maintenance inhalers. A contributing cause is lack of proper education for both the caregivers and their patients. All too often proper instructions were not given when the drug was first prescribed. And even when they are provided, patients sometimes don't really understand, or they forget. Either way, having similar inhalers for different purposes is an invitation to error. (This was less likely to be a problem when the drug was studied by the drug companies; see YELLOW BOX above, under 'DPI Type 2'.)

The problem is compounded when patients are on multiple inhalers, eg, Proventil for rescue, Advair and Spiriva for maintenance. That's 3 separate devices with two different purposes -- easy for the patient to get confused. (Pills and capsules come in many colors and sizes, but they are all swallowed the same way.) What's needed is a universal delivery device for all inhalers, with perhaps just two colors: red for rescue drugs and green for maintenance drugs.

Anyone with clinical interest in the inhaler problems discussed above (Errors 1 & 2) should definitely read Problems With Inhaler Use: A Call for Improved Clinician and Patient Education, by James B. Fink and Bruck K. Rubin (Respiratory Care, Sept 2005, Vol 50, No. 10, pages 1360-75).

3. Not checking some objective measurement of the patient's air flow obstruction.

Every patient should have a breathing test to ascertain the degree of

impairment caused by the asthma. The most frequently performed

test is 'spirometry', which takes just a few minutes and requires the

patient to exhale forcefully thru a testing device (shown below).

A patient performing the spirometry test

A patient performing the spirometry test

Graphs from a normal spirometry test; left panel, graph of flow vs. volume; right panel, graph of time vs. volume.

Spirometry can be a valuable test in diagnosing and managing respiratory

patients. The following article (in 2 parts) is for respiratory therapists, nurses,

physicians and anyone else who may be responsible for ordering and/or interpreting

spirometry.

The Value of Spirometry

in Clinical Practice, Part 1, June 2010

The Value of Spirometry in Clinical Practice, Part 2, July 2010

4. Missing the diagnosis of asthma because of

"clear lung fields" on exam.

A patient can have clear lungs if the exam is done

only during quiet breathing. The examiner places the

stethoscope over the lungs and pronounces them 'clear -

no wheezing.' In fact wheezing may be heard, but only after

a deep breath followed by a forceful exhalation.

Here the problem is simply an inexperienced care giver

(physician, nurse, nurse practioner, etc.).

Many asthmatics with 'clear lung fields' on exam in

fact have wheezes that are claerly heard only at

the end of a forced exhalation.

5. Smoking while suffering from asthma.

I see many patients who continue to smoke while complaining

of cough or shortness of breath. Sure, they admit to

being addicted, or "I just can't stop", but there is still no

excuse. Smoking could be a major contributor to episodes of

wheezing and shortness of breath (what we generally call 'acute bronchitis').

Also, smoking greatly retards recovery,

since cigarette smoke impairs clearing of mucus from

the lungs. I tell my patients it's like complaining of

a headache while banging your head with a hammer. Duh!

6. Fear of prescribing oral steroids.

Doctors are often reluctant to prescribe oral steroid medication (prednisone, methylprednisolone),

yet many times it is the only drug that will effectively treat

the patient's asthma. Instead, all too often physicians prescribe the latest inhaled

steroid (IS) or long acting bronchodilator (LABD) or a combination IS+LABD inhaler.

These drugs (all non-generic and expensive) have a definite role in asthma treatment maintenance,

but not in treating the patient whose symptoms are acute, progressive or interfering with

daily activity.

If a patient in the office has wheezing and/or asthma symptoms interfering with daily

acivity, I will usually prescribe a 'tapering' course of prednisone, e.g.

- 20 mg tablets 3 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets 2 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets one a day for 3-5 days, then the drug is discontinued

This 9 to 11 day course is safe and does not lead to the long term side effects of steroids that are rightly feared: weight gain, diabetes, weakening of bones, eye probems. More often than not patients will respond with elimination of symptoms and wheezing. At that point decision can be made about continuing treatment with inhaled medication.

7. Over-using antibiotics to treat asthma.

In adults, bacterial infections are almost never the cause

of asthma exacerbations, and antibiotics are rarely needed. The

most common triggers of an asthma attack in adults are

viral infection, allergens (pollen, animal fur, etc.),

and irritants (fumes, dusts, etc.), none of which responds to

an antibiotic. An antibiotic may be needed if the

patient has sinusitis or smoking-related chronic bronchitis.

8. Not looking for other causes or precipitants of

wheezing and shortness of breath when asthma medication

is ineffective.

Asthma starts in the lungs and almost always leads to wheezing.

However, not all wheezing starts in the lungs or is 'asthma';

The problem may arise elsewhere in the body. Examples:

- Congestive heart failure is fluid buildup in the lungs from heart disease,

which can then cause wheezing. Diagnosis is usually not

difficult, and starts with a detailed history, physical exam and

chest x-ray. Treatment of so-called 'cardiac asthma' is different

than traditional asthma, and must be directed to the heart problem.

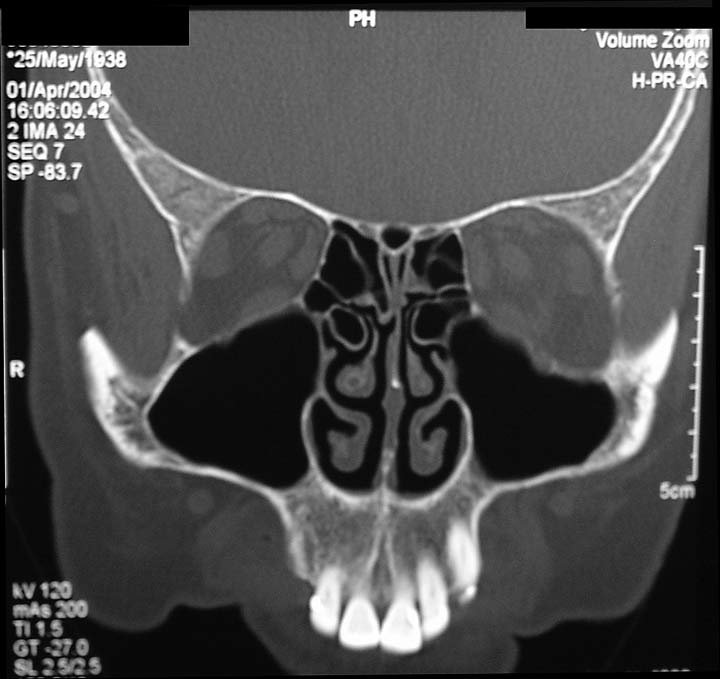

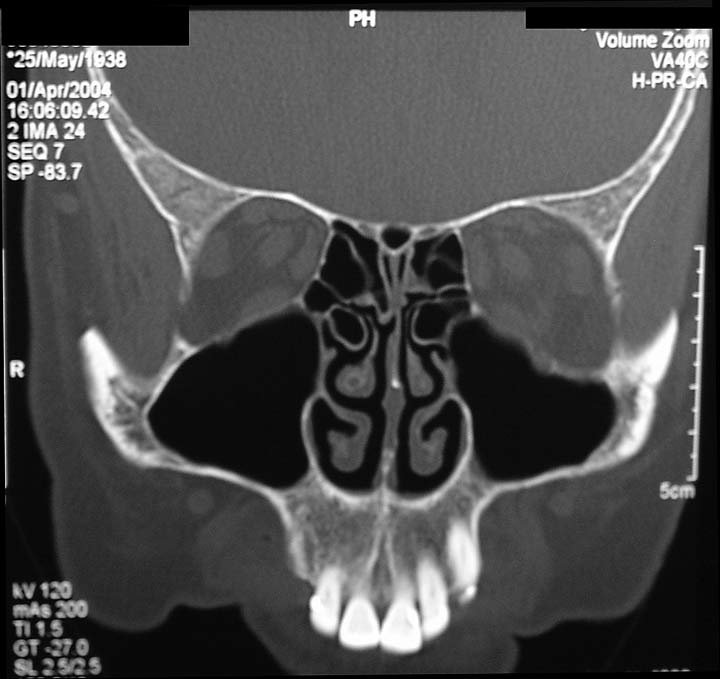

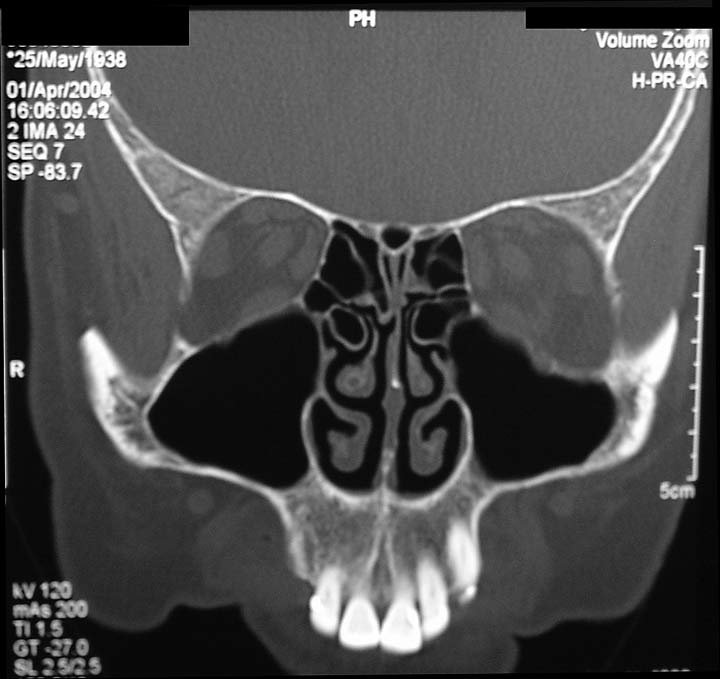

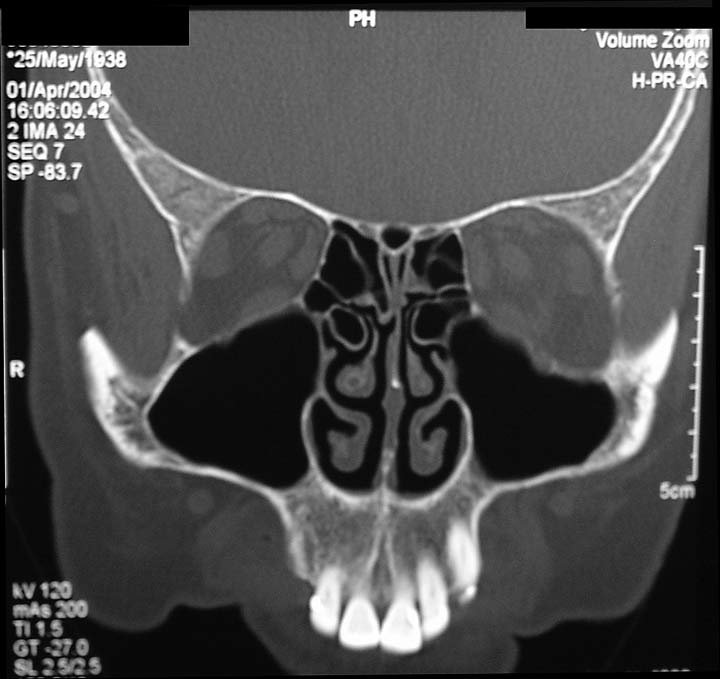

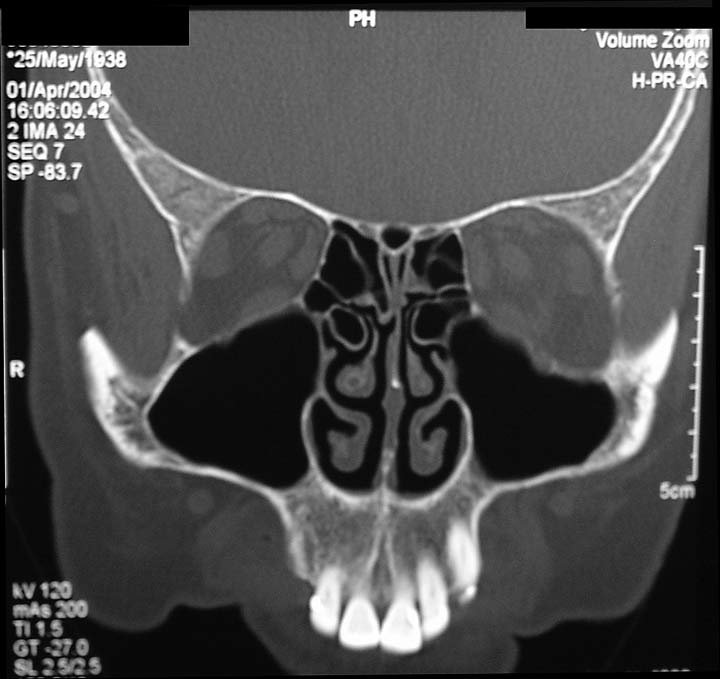

- Sinusitis is often present in many chronic asthmatic

conditions, and requires treatment before the asthma can

be improved; the best test to uncover sinusitis is a sinus

CT scan. The figures below illustrate sinusitis, which

can either lead to asthma or cause asthma symptoms to continue despite treatment.

The drawing shows mucous in the left maxillary sinus (behind the left cheek bone).

The sinus CT scan below the drawing shows extensive mucous in the patient's right maxillary sinus (patient facing you),

and also a lesser amount of mucous in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

- Acid reflux can cause wheezing by spilling over of acid

from the stomach into the lungs. In addition to treating the asthma

medication is used to help control the acid (eg, proton

pump inhibitors). In the most severe cases the patient may

need a surgical procedure to prevent the acid reflux

- Upper airway obstruction can cause wheezing. Here the

problem is in the neck area (trachea, voice box),

not the lungs. Tumors, vocal cord disease and other conditions

in the upper airway can causes wheezes that sound like they are

coming from the lungs; treatment with asthma medications usually

has no benefit.

9. Not considering environmental factors in managing

asthma.

Occupational asthma

is a common problem, and should always

be considered when evaluating an adult with asthma.

The home environment (plants, animals, molds)

may also trigger an asthma attack, either thru

direct irritation or via an allergy mechanism. While

treatment is usually the same regardless of

precipitating causes, if triggers can be identified it

is of paramount importance to avoid them. This may be

difficult if one's livelihood is causing asthma, or even one's pets.

(I have been more successful in getting patients to change

offending jobs than in getting rid of offending pets.)

10. Letting the asthma attack continue

without getting proper treatment, or substituting holistic treatment for medication.

In fact, many patients suffer too long before seeking medical

treatment. The longer the asthma attack continues the more

refractory it becomes. Patients have died because they didn't

seek medical attention for symptoms that lasted days.

After seeing a physician for treatment,

patients must be encouraged to either call if they are

not responding or go to an urgent care center or

emergency department if they are getting worse.

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet.

An excellent review of natural remedies is found at

About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies

always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma,

it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed.

Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for

other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow

obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

About.com lists 8 alternative remedies for asthma. One in particular that has received much attention is the

Buteyko breathing method. This is based

on the false assumption that hyperventilation -- literally, blowing off CO2 -- perpetuates asthma, and that by controlling

one's breathing, asthma can be controlled or improved. This techniqe was developed by Russian-born researcher Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko.

It consists of shallow-breathing exercises designed to help people with asthma breathe easier. According to

About.com:

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma.

Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal.

Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work.

National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines

state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing

techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy

an

e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you

have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want

to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine.

Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically,

pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to:

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page |

10 Common Errors in COPD Management |

Chronic Cough home page |

Lakesidepress home page |

Subject Index for all web

sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012

The Value of Spirometry in Clinical Practice, Part 1, June 2010

The Value of Spirometry in Clinical Practice, Part 2, July 2010

4. Missing the diagnosis of asthma because of "clear lung fields" on exam.

A patient can have clear lungs if the exam is done

only during quiet breathing. The examiner places the

stethoscope over the lungs and pronounces them 'clear -

no wheezing.' In fact wheezing may be heard, but only after

a deep breath followed by a forceful exhalation.

Here the problem is simply an inexperienced care giver

(physician, nurse, nurse practioner, etc.).

Many asthmatics with 'clear lung fields' on exam in

fact have wheezes that are claerly heard only at

the end of a forced exhalation.

5. Smoking while suffering from asthma.

I see many patients who continue to smoke while complaining

of cough or shortness of breath. Sure, they admit to

being addicted, or "I just can't stop", but there is still no

excuse. Smoking could be a major contributor to episodes of

wheezing and shortness of breath (what we generally call 'acute bronchitis').

Also, smoking greatly retards recovery,

since cigarette smoke impairs clearing of mucus from

the lungs. I tell my patients it's like complaining of

a headache while banging your head with a hammer. Duh!

6. Fear of prescribing oral steroids.

Doctors are often reluctant to prescribe oral steroid medication (prednisone, methylprednisolone),

yet many times it is the only drug that will effectively treat

the patient's asthma. Instead, all too often physicians prescribe the latest inhaled

steroid (IS) or long acting bronchodilator (LABD) or a combination IS+LABD inhaler.

These drugs (all non-generic and expensive) have a definite role in asthma treatment maintenance,

but not in treating the patient whose symptoms are acute, progressive or interfering with

daily activity.

If a patient in the office has wheezing and/or asthma symptoms interfering with daily

acivity, I will usually prescribe a 'tapering' course of prednisone, e.g.

- 20 mg tablets 3 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets 2 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets one a day for 3-5 days, then the drug is discontinued

This 9 to 11 day course is safe and does not lead to the long term side effects of steroids that are rightly feared: weight gain, diabetes, weakening of bones, eye probems. More often than not patients will respond with elimination of symptoms and wheezing. At that point decision can be made about continuing treatment with inhaled medication.

7. Over-using antibiotics to treat asthma.

In adults, bacterial infections are almost never the cause

of asthma exacerbations, and antibiotics are rarely needed. The

most common triggers of an asthma attack in adults are

viral infection, allergens (pollen, animal fur, etc.),

and irritants (fumes, dusts, etc.), none of which responds to

an antibiotic. An antibiotic may be needed if the

patient has sinusitis or smoking-related chronic bronchitis.

8. Not looking for other causes or precipitants of

wheezing and shortness of breath when asthma medication

is ineffective.

Asthma starts in the lungs and almost always leads to wheezing.

However, not all wheezing starts in the lungs or is 'asthma';

The problem may arise elsewhere in the body. Examples:

- Congestive heart failure is fluid buildup in the lungs from heart disease,

which can then cause wheezing. Diagnosis is usually not

difficult, and starts with a detailed history, physical exam and

chest x-ray. Treatment of so-called 'cardiac asthma' is different

than traditional asthma, and must be directed to the heart problem.

- Sinusitis is often present in many chronic asthmatic

conditions, and requires treatment before the asthma can

be improved; the best test to uncover sinusitis is a sinus

CT scan. The figures below illustrate sinusitis, which

can either lead to asthma or cause asthma symptoms to continue despite treatment.

The drawing shows mucous in the left maxillary sinus (behind the left cheek bone).

The sinus CT scan below the drawing shows extensive mucous in the patient's right maxillary sinus (patient facing you),

and also a lesser amount of mucous in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

- Acid reflux can cause wheezing by spilling over of acid

from the stomach into the lungs. In addition to treating the asthma

medication is used to help control the acid (eg, proton

pump inhibitors). In the most severe cases the patient may

need a surgical procedure to prevent the acid reflux

- Upper airway obstruction can cause wheezing. Here the

problem is in the neck area (trachea, voice box),

not the lungs. Tumors, vocal cord disease and other conditions

in the upper airway can causes wheezes that sound like they are

coming from the lungs; treatment with asthma medications usually

has no benefit.

9. Not considering environmental factors in managing

asthma.

Occupational asthma

is a common problem, and should always

be considered when evaluating an adult with asthma.

The home environment (plants, animals, molds)

may also trigger an asthma attack, either thru

direct irritation or via an allergy mechanism. While

treatment is usually the same regardless of

precipitating causes, if triggers can be identified it

is of paramount importance to avoid them. This may be

difficult if one's livelihood is causing asthma, or even one's pets.

(I have been more successful in getting patients to change

offending jobs than in getting rid of offending pets.)

10. Letting the asthma attack continue

without getting proper treatment, or substituting holistic treatment for medication.

In fact, many patients suffer too long before seeking medical

treatment. The longer the asthma attack continues the more

refractory it becomes. Patients have died because they didn't

seek medical attention for symptoms that lasted days.

After seeing a physician for treatment,

patients must be encouraged to either call if they are

not responding or go to an urgent care center or

emergency department if they are getting worse.

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet.

An excellent review of natural remedies is found at

About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies

always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma,

it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed.

Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for

other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow

obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

About.com lists 8 alternative remedies for asthma. One in particular that has received much attention is the

Buteyko breathing method. This is based

on the false assumption that hyperventilation -- literally, blowing off CO2 -- perpetuates asthma, and that by controlling

one's breathing, asthma can be controlled or improved. This techniqe was developed by Russian-born researcher Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko.

It consists of shallow-breathing exercises designed to help people with asthma breathe easier. According to

About.com:

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma.

Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal.

Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work.

National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines

state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing

techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy

an

e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you

have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want

to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine.

Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically,

pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to:

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page |

10 Common Errors in COPD Management |

Chronic Cough home page |

Lakesidepress home page |

Subject Index for all web

sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012

6. Fear of prescribing oral steroids.

Doctors are often reluctant to prescribe oral steroid medication (prednisone, methylprednisolone),

yet many times it is the only drug that will effectively treat

the patient's asthma. Instead, all too often physicians prescribe the latest inhaled

steroid (IS) or long acting bronchodilator (LABD) or a combination IS+LABD inhaler.

These drugs (all non-generic and expensive) have a definite role in asthma treatment maintenance,

but not in treating the patient whose symptoms are acute, progressive or interfering with

daily activity.

If a patient in the office has wheezing and/or asthma symptoms interfering with daily

acivity, I will usually prescribe a 'tapering' course of prednisone, e.g.

- 20 mg tablets 3 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets 2 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets one a day for 3-5 days, then the drug is discontinued

This 9 to 11 day course is safe and does not lead to the long term side effects of steroids that are rightly feared: weight gain, diabetes, weakening of bones, eye probems. More often than not patients will respond with elimination of symptoms and wheezing. At that point decision can be made about continuing treatment with inhaled medication.

7. Over-using antibiotics to treat asthma.

In adults, bacterial infections are almost never the cause

of asthma exacerbations, and antibiotics are rarely needed. The

most common triggers of an asthma attack in adults are

viral infection, allergens (pollen, animal fur, etc.),

and irritants (fumes, dusts, etc.), none of which responds to

an antibiotic. An antibiotic may be needed if the

patient has sinusitis or smoking-related chronic bronchitis.

8. Not looking for other causes or precipitants of

wheezing and shortness of breath when asthma medication

is ineffective.

Asthma starts in the lungs and almost always leads to wheezing.

However, not all wheezing starts in the lungs or is 'asthma';

The problem may arise elsewhere in the body. Examples:

- Congestive heart failure is fluid buildup in the lungs from heart disease,

which can then cause wheezing. Diagnosis is usually not

difficult, and starts with a detailed history, physical exam and

chest x-ray. Treatment of so-called 'cardiac asthma' is different

than traditional asthma, and must be directed to the heart problem.

- Sinusitis is often present in many chronic asthmatic

conditions, and requires treatment before the asthma can

be improved; the best test to uncover sinusitis is a sinus

CT scan. The figures below illustrate sinusitis, which

can either lead to asthma or cause asthma symptoms to continue despite treatment.

The drawing shows mucous in the left maxillary sinus (behind the left cheek bone).

The sinus CT scan below the drawing shows extensive mucous in the patient's right maxillary sinus (patient facing you),

and also a lesser amount of mucous in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

- Acid reflux can cause wheezing by spilling over of acid

from the stomach into the lungs. In addition to treating the asthma

medication is used to help control the acid (eg, proton

pump inhibitors). In the most severe cases the patient may

need a surgical procedure to prevent the acid reflux

- Upper airway obstruction can cause wheezing. Here the

problem is in the neck area (trachea, voice box),

not the lungs. Tumors, vocal cord disease and other conditions

in the upper airway can causes wheezes that sound like they are

coming from the lungs; treatment with asthma medications usually

has no benefit.

9. Not considering environmental factors in managing

asthma.

Occupational asthma

is a common problem, and should always

be considered when evaluating an adult with asthma.

The home environment (plants, animals, molds)

may also trigger an asthma attack, either thru

direct irritation or via an allergy mechanism. While

treatment is usually the same regardless of

precipitating causes, if triggers can be identified it

is of paramount importance to avoid them. This may be

difficult if one's livelihood is causing asthma, or even one's pets.

(I have been more successful in getting patients to change

offending jobs than in getting rid of offending pets.)

10. Letting the asthma attack continue

without getting proper treatment, or substituting holistic treatment for medication.

In fact, many patients suffer too long before seeking medical

treatment. The longer the asthma attack continues the more

refractory it becomes. Patients have died because they didn't

seek medical attention for symptoms that lasted days.

After seeing a physician for treatment,

patients must be encouraged to either call if they are

not responding or go to an urgent care center or

emergency department if they are getting worse.

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet.

An excellent review of natural remedies is found at

About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies

always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma,

it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed.

Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for

other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow

obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

About.com lists 8 alternative remedies for asthma. One in particular that has received much attention is the

Buteyko breathing method. This is based

on the false assumption that hyperventilation -- literally, blowing off CO2 -- perpetuates asthma, and that by controlling

one's breathing, asthma can be controlled or improved. This techniqe was developed by Russian-born researcher Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko.

It consists of shallow-breathing exercises designed to help people with asthma breathe easier. According to

About.com:

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma.

Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal.

Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work.

National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines

state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing

techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy

an

e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you

have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want

to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine.

Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically,

pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to:

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page |

10 Common Errors in COPD Management |

Chronic Cough home page |

Lakesidepress home page |

Subject Index for all web

sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012

- 20 mg tablets 3 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets 2 times a day for 3 days, then

- 20 mg tablets one a day for 3-5 days, then the drug is discontinued

7. Over-using antibiotics to treat asthma.

In adults, bacterial infections are almost never the cause

of asthma exacerbations, and antibiotics are rarely needed. The

most common triggers of an asthma attack in adults are

viral infection, allergens (pollen, animal fur, etc.),

and irritants (fumes, dusts, etc.), none of which responds to

an antibiotic. An antibiotic may be needed if the

patient has sinusitis or smoking-related chronic bronchitis.

8. Not looking for other causes or precipitants of

wheezing and shortness of breath when asthma medication

is ineffective.

Asthma starts in the lungs and almost always leads to wheezing.

However, not all wheezing starts in the lungs or is 'asthma';

The problem may arise elsewhere in the body. Examples:

- Congestive heart failure is fluid buildup in the lungs from heart disease,

which can then cause wheezing. Diagnosis is usually not

difficult, and starts with a detailed history, physical exam and

chest x-ray. Treatment of so-called 'cardiac asthma' is different

than traditional asthma, and must be directed to the heart problem.

- Sinusitis is often present in many chronic asthmatic

conditions, and requires treatment before the asthma can

be improved; the best test to uncover sinusitis is a sinus

CT scan. The figures below illustrate sinusitis, which

can either lead to asthma or cause asthma symptoms to continue despite treatment.

The drawing shows mucous in the left maxillary sinus (behind the left cheek bone).

The sinus CT scan below the drawing shows extensive mucous in the patient's right maxillary sinus (patient facing you),

and also a lesser amount of mucous in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

- Acid reflux can cause wheezing by spilling over of acid

from the stomach into the lungs. In addition to treating the asthma

medication is used to help control the acid (eg, proton

pump inhibitors). In the most severe cases the patient may

need a surgical procedure to prevent the acid reflux

- Upper airway obstruction can cause wheezing. Here the

problem is in the neck area (trachea, voice box),

not the lungs. Tumors, vocal cord disease and other conditions

in the upper airway can causes wheezes that sound like they are

coming from the lungs; treatment with asthma medications usually

has no benefit.

9. Not considering environmental factors in managing

asthma.

Occupational asthma

is a common problem, and should always

be considered when evaluating an adult with asthma.

The home environment (plants, animals, molds)

may also trigger an asthma attack, either thru

direct irritation or via an allergy mechanism. While

treatment is usually the same regardless of

precipitating causes, if triggers can be identified it

is of paramount importance to avoid them. This may be

difficult if one's livelihood is causing asthma, or even one's pets.

(I have been more successful in getting patients to change

offending jobs than in getting rid of offending pets.)

10. Letting the asthma attack continue

without getting proper treatment, or substituting holistic treatment for medication.

In fact, many patients suffer too long before seeking medical

treatment. The longer the asthma attack continues the more

refractory it becomes. Patients have died because they didn't

seek medical attention for symptoms that lasted days.

After seeing a physician for treatment,

patients must be encouraged to either call if they are

not responding or go to an urgent care center or

emergency department if they are getting worse.

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet.

An excellent review of natural remedies is found at

About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies

always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma,

it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed.

Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for

other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow

obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

About.com lists 8 alternative remedies for asthma. One in particular that has received much attention is the

Buteyko breathing method. This is based

on the false assumption that hyperventilation -- literally, blowing off CO2 -- perpetuates asthma, and that by controlling

one's breathing, asthma can be controlled or improved. This techniqe was developed by Russian-born researcher Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko.

It consists of shallow-breathing exercises designed to help people with asthma breathe easier. According to

About.com:

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma.

Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal.

Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work.

National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines

state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing

techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy

an

e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you

have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want

to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine.

Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically,

pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to:

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page |

10 Common Errors in COPD Management |

Chronic Cough home page |

Lakesidepress home page |

Subject Index for all web

sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012

- Congestive heart failure is fluid buildup in the lungs from heart disease, which can then cause wheezing. Diagnosis is usually not difficult, and starts with a detailed history, physical exam and chest x-ray. Treatment of so-called 'cardiac asthma' is different than traditional asthma, and must be directed to the heart problem.

- Sinusitis is often present in many chronic asthmatic

conditions, and requires treatment before the asthma can

be improved; the best test to uncover sinusitis is a sinus

CT scan. The figures below illustrate sinusitis, which

can either lead to asthma or cause asthma symptoms to continue despite treatment.

The drawing shows mucous in the left maxillary sinus (behind the left cheek bone).

The sinus CT scan below the drawing shows extensive mucous in the patient's right maxillary sinus (patient facing you),

and also a lesser amount of mucous in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

Left image: normal CT scan of sinuses. Right image: CT scan showing maxillary sinusitis, with large fluid collection in the patient's right maxillary sinus and lesser amount of fluid in the left maxillary sinus.

- Acid reflux can cause wheezing by spilling over of acid from the stomach into the lungs. In addition to treating the asthma medication is used to help control the acid (eg, proton pump inhibitors). In the most severe cases the patient may need a surgical procedure to prevent the acid reflux

- Upper airway obstruction can cause wheezing. Here the problem is in the neck area (trachea, voice box), not the lungs. Tumors, vocal cord disease and other conditions in the upper airway can causes wheezes that sound like they are coming from the lungs; treatment with asthma medications usually has no benefit.

9. Not considering environmental factors in managing asthma.

Occupational asthma

is a common problem, and should always

be considered when evaluating an adult with asthma.

The home environment (plants, animals, molds)

may also trigger an asthma attack, either thru

direct irritation or via an allergy mechanism. While

treatment is usually the same regardless of

precipitating causes, if triggers can be identified it

is of paramount importance to avoid them. This may be

difficult if one's livelihood is causing asthma, or even one's pets.

(I have been more successful in getting patients to change

offending jobs than in getting rid of offending pets.)

10. Letting the asthma attack continue

without getting proper treatment, or substituting holistic treatment for medication.

In fact, many patients suffer too long before seeking medical

treatment. The longer the asthma attack continues the more

refractory it becomes. Patients have died because they didn't

seek medical attention for symptoms that lasted days.

After seeing a physician for treatment,

patients must be encouraged to either call if they are

not responding or go to an urgent care center or

emergency department if they are getting worse.

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet.

An excellent review of natural remedies is found at

About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies

always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma,

it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed.

Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for

other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow

obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

About.com lists 8 alternative remedies for asthma. One in particular that has received much attention is the

Buteyko breathing method. This is based

on the false assumption that hyperventilation -- literally, blowing off CO2 -- perpetuates asthma, and that by controlling

one's breathing, asthma can be controlled or improved. This techniqe was developed by Russian-born researcher Konstantin Pavlovich Buteyko.

It consists of shallow-breathing exercises designed to help people with asthma breathe easier. According to

About.com:

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma.

Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal.

Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work.

National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines

state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing

techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy

an

e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you

have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want

to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine.

Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically,

pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to:

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page |

10 Common Errors in COPD Management |

Chronic Cough home page |

Lakesidepress home page |

Subject Index for all web

sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012

There are also plentiful "natural remedies" or "holistic treatments" for asthma, promulgated in books and on the internet. An excellent review of natural remedies is found at About.com: Natural Remedies for Asthma. Good web sites about natural or holistic remedies always carry a disclaimer, such as About.com's: "If you are experiencing symptoms of asthma, it's important to see your doctor to be properly diagnosed. Although alternative therapies haven't been shown to be as promising for asthma as they have for other conditions..."

The problem with alternative remedies is two-fold:

- They are not proven effective for people with air flow obstruction;

- They may give a false sense of security while the asthma either doesn't improve or worsens.

"The Buteyko Breathing Technique is based on the premise that raising blood levels of carbon dioxide through shallow breathing can help people with asthma. Carbon dioxide is believed to dilate the smooth muscles of the airways."

That explanation is physiologic nonsense, not least because people cannot elevate their CO2 level to above normal. Furthermore, the Buteyko method has never been proven to work. National Institutes of Health Asthma Guidelines state: "The Expert Panel concludes there is insufficient evidence to suggest that breathing techniques provide clinical benefit to patients who have asthma." Yet the myth persists, and you can even buy an e-book on the technique at Amazon.com.

Note that critcism of Buteyko and other alternative treatments pertains to symptomatic asthma. If you have a history of asthma, but are not currently having symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing), and want to use an holistic method for relaxation or to reduce stress, that's fine. Another breathing technique promulgated for this purpose is yoga (specifically, pranayama).

Books About Asthma and Sinusitis

(With links to Amazon.com. Books listed in reverse order of publication)

92 Tips for Dealing with the Symptoms and Treatment of Asthma, by Emily Kingfisher, Create Space, 2010.

No More allergies, asthma, or sinus infections,

Dr. Lon Jones, Freedom Press, 2010.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

The Allergy and Asthma Cure: A

Complete 8-Step Nutritional Program, Fred Pescatore, MD, Wiley,

2008.

Asthma-free naturally ,

Patrick McKeown, Conari Press, 2008.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed.,

Francis V.Adams, MD, McGraw Hill Books, 2007.

The Sinus Cure: 7 Simple Steps to Relieve

Sinusitis and Other Ear, Nose and Throat Conditions,

Debra Fulghum Bruce PhD and Murray Grossan, MD, Ballantine

Books, 2007.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Sinus Relief Now: The Groundbreaking 5-Step

Program for Sinus, Allergy and Asthma Sufferers, Jordan S. Josephson, MD,

Perigee Trade, 2006.

Asthma for Dummies, William

E. Berger, MD, For Dummies, 2004.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

The Children's Hospital Guide to Asthma,

Julian Lewis Allen, editor. Wiley, 2004.

The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing

Your Sinuses, Ralph B. Metson, MD, and Steven Mardon,

McGraw Hill, 2004.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control

of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan

Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

The Harvard medical School Guide to Taking Control of Asthma, Christopher H. Fanta, Lynda M. Cristiano, Kenan Hayer, Free Press, 2003.

Forward any comments to: Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Asthma home page | 10 Common Errors in COPD Management | Chronic Cough home page | Lakesidepress home page | Subject Index for all web sites

Copyright © Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Initially posted December 2008; Last revised December 21, 2012