Program Notes: The following information (in the red-bordered area) is in the playbill given to the audience as they enter the auditorium.

[Stage directions in Courier font]

As audience is being seated and until the play begins, information about this night’s performance is projected on rear screen, along with a picture of General Sherman. Subsequent pictures are projected on rear screen to coincide with dialogue in script.

ACT 1 Setting: Masonic Hall auditorium, Savannah, Ga. Date: September 10, 1875

Off stage narrator speaks:

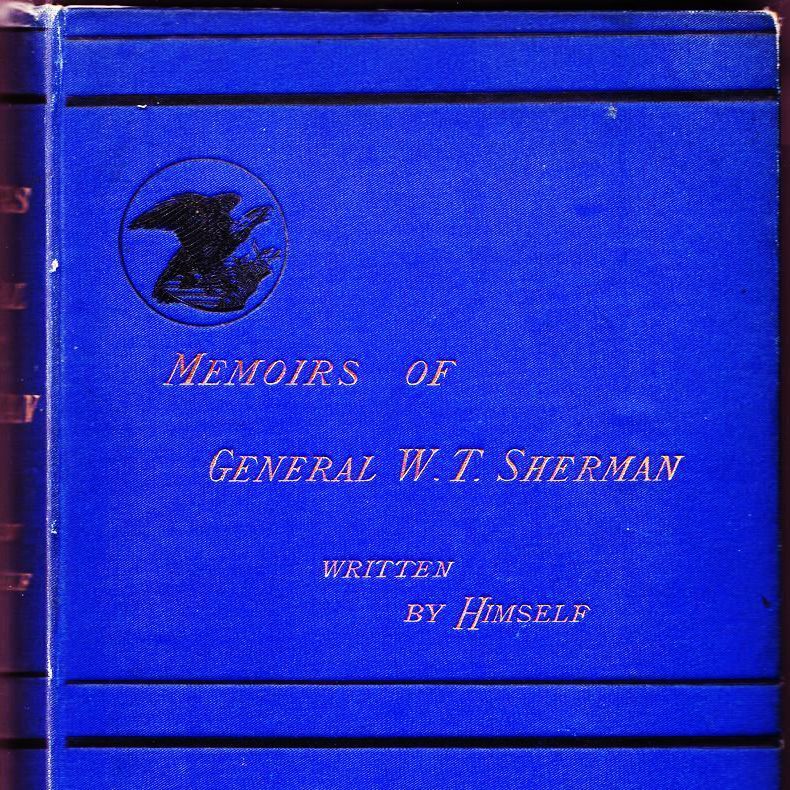

Ladies and Gentleman of Savannah, I am pleased to announce tonight’s very special speaker, General William Tecumseh Sherman. As most of you surely know, General Sherman led his 62,000-man army from Atlanta to Savannah in the fall of 1864. They reached Savannah December 21, 1864 and occupied our lovely city until January 21, 1865. After leaving Savannah his army marched through the Carolinas. Along with General Ulysses S. Grant’s victories in Virginia, Sherman’s long southern march helped to end the Civil War. He is here to talk about his new book, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman. This is the first book written by any Civil War general, on either side. General Sherman, welcome back to Savannah!

Applause

Sherman walks up to the podium to address the audience. He is dressed in civilian clothes.

Thank you, thank you. My Memoirs were published the end of January, 10 years to the day since I left Savannah for my Carolina campaign. This is my first trip back, and I am happy to be here. I have no ill feelings toward Savannah or its citizens, and trust you have none toward me, though I am sure some of you must harbor such feelings. And I assume some of you are asking why old Tecumseh is even coming back to Savannah. Didn’t he do enough damage the first time through? Well, allow me to explain.The book covers my adult life, and of course a good portion of it – maybe half – deals with the Civil War period. The publisher suggested I go on a speaking tour to promote the book, to which I readily agreed, seeing as he promised to foot the expenses.

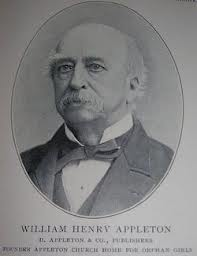

The publisher’s name is William Henry Appleton and he’s a good and fair businessman. His father Daniel founded D. Appleton and Company, one of the nation’s premier publishers.

Sherman turns to look at projected photo of William Appleton.

There you see a picture of my publisher, Mr. William Appleton, taken just this year. The photograph is by Matthew Brady, who also took many photos during the war. Mr. Appleton’s actually a jolly fellow, though for some reason he couldn’t bring himself to smile for the camera.

…I told Mr. Appleton that opening in Savannah would likely generate the most publicity, both north and south. And tonight I see reporters here from the New York Times, the New York Tribune and the Philadelphia Enquirer, so I think I was right on that issue. Opening this tour in New York would not get much attention in the south and west, whereas reviews from Savannah ---- well, that’s special. Readers of northern papers will surely be curious about this fellow Sherman returning to the scene of his crimes.

Sherman lets out a chuckle.

Sherman turns to look at screen, as if to satisfy himself the right photo is in place.

My Memoirs begin with the year 1846, when our country fought its war with Mexico. From there I discuss my years as a private citizen, and then how I became re-involved with the army. It’s an important period of my life and you can read about it, but I know what you’re most interested in, and it’s frankly what I’m most interested in telling. How I came to march my army from Atlanta to Savannah. What really happened to Georgia’s citizens on the march. My attitude toward the South and to Negroes in particular. What we did to help preserve Savannah from destruction. How Savannah’s citizens reacted to the occupation. And why I believe my actions helped shorten the war.

I know many of you lost loved ones in the Civil War, and that there is no accounting for the loss. You have my condolences, which may ring hollow since many soldiers died in battles that I led. Even more soldiers died from disease, simply the result of being out in the open and exposed to illnesses we had no treatment for. That is war, and it is never pretty. My own son died of typhoid fever after my family visited me near Vicksburg in 1863. Willy and he was only nine years old.

Sherman pauses for a second, briefly overcome with emotion, then quickly continues.

Another son died December 4, 1864, while I was marching to Savannah. Charles was his name, only 6 months old. I never saw him, and could not even be with my wife to console her. I mention these losses to lay aside any impression that I am cold-hearted and tin-eared about human suffering. I am not. I know the pain of losing loved ones.

As I have said many times, war is cruelty and you cannot refine it. It is painful and hellish and an affliction of mankind. I went to West Point never dreaming I would one day fight against fellow countrymen to preserve the Union. I grew up in Lancaster, Ohio. My father died when I was only nine. I went to live with a close family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing. Ewing became a United States senator from Ohio, and his political connections secured me the appointment to West Point. So I went off to college at age 16. It was a good education, I won’t deny that, and free. This picture you see is not my graduating class, for there were no photographs taken of my 1840 West Point class. This picture is of a recent class of cadets, taken after the Civil War. Many Civil War Generals, both Union and Confederate, graduated from West Point. There are so many stories to tell.

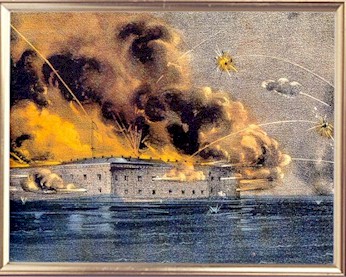

Here’s one anecdote. Major Robert Anderson, in charge of Fort Sumter the day it was bombarded, April 12, 1861, had been the artillery instructor at West Point of one P.T. Beauregard. Beauregard, you may recall, was the Confederate general who gave the order to shell the fort, which started the Civil War. Major Anderson had taught him well, at least about artillery, although perhaps not enough about discretion.

Anyway, I graduated at age 20, and then spent my early army years in the South, in Florida, Louisiana, Charleston.

In my southern travels I came through Savannah two or three times and stayed at the Pulaski House Hotel over on Bryan and Bull Streets. I believe this photo is actually from the 1850s. Anyway, Pulaski House remains a fine establishment, and I am staying there again while in Savannah.

In 1850 I married Thomas Ewing’s daughter Ellen, and am proud to say the ceremony was attended by none other than President Zachary Taylor. Thomas Ewing by that time was Secretary of the Interior.

Sherman turns briefly to look at portrait of Ellen Sherman.

This is a fine portrait of my wife Ellen. We had a total of 8 children, two of whom died young, so 6 are living.

Continued...

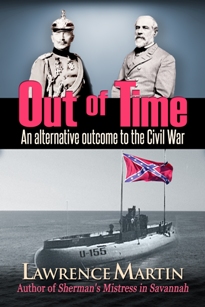

In this 2-Act play General Sherman discusses the burning of Atlanta, defends the infamous March to the Sea and his treatment of Negroes, and has much to say about the occupation of Savannah and War Secretary Edwin Stanton (who met with Sherman in Savannah). There are 5 actors and numerous period photos to engage the audience. The complete manuscript, with all stage directions and photos, is available to anyone interested in producing the play (amateur or professional production).

Lawrence Martin

January, 2013