Secrets of the best

golfers -- from a

professionaland agolfer

The title is a fraud. Go back and read it closely! I am a professional, that's true: a licensed medical physician. And I am surely a golfer. My double digit handicap belies the many hours spent trying to tame inconsistency. But I am not a professional golfer - as in one who plays or teaches golf for a living. No way.But wait! Now that I have your attention I do have some 'secrets' to tell. They pertain to all the best golfers in the world. I don't mean just the touring pros, but all players who can get around the course with a par score or close to it. (I develop and explain each secret at some length in this essay, and provide many interesting golf links. If you don't have time to read the full essay, and want just a summary, please click here.) These secrets are really 'truths' about what it takes to become a good player. I call them secrets because they are 'hidden' from the millions of people who, like me, started golf as adults (often in middle age), and aspire to become better players. These people -- who spend gazillions on equipment, lessons, magazines, books, and assorted paraphernalia -- are the ones for whom this is written. The secrets were never told to me by anyone; instead, I learned them gradually in a years'-long quest to get my handicap south of 20: by asking questions of good players (including pros), by reading first person accounts, and by simple observation. That these secrets may seem intuitive or obvious when stated does not mean the average golfer is aware of them. Quite the contrary. The average golfer is under the influence of the 'you-can-get-better-here-is-all-you-need' mentality pervasive in the golf world. Learn this swing tip, buy this new driver, get this new laser gizmo, subscribe to this magazine, go to this golf school, watch this video -- do these things and you will improve! The golf secrets I have learned belie this mentality. And here is the greatest paradox of all: once you come to accept these secrets as basic truths, you may be in a better position to improve your game. (If you are a scratch golfer or think you don't need to get any better, you can quit reading now. And if you think there is only some mechanical swing maneuver between you and golf Nirvana, more power to you.) I have found the secrets confirmed in books by players whose quest for improvement was interesting enough to write about (and get published). You surely won't find them stated in the popular golf media, or by professionals who write or speak for these media. The main reason, I think, is because the secrets make golf seem far more difficult than purveyors of equipment, golf travel, golf lessons and golf magazines care to admit. But this is not an advertisement and I won't beat around the bush any longer. (The

"Ads by Google" placed at top and bottom are to help defray the cost of web site maintenance. It should be apparent that they have no influence on the content of this web site.)

Here are the four secrets. As you read through the discussion of each one, please remember:

you will likely never see them highlighted in the popular golf media.

No later than 15, and preferably before puberty. When you start as a full-fledged adult you have almost zero chance of becoming a top golfer. The later you start playing, the harder the game is to learn. This fact is surely known to most golf instructors, yet almost never talked about. Tiger Woods started at age 2, Arnold Palmer at 4, Francis Ouimet at 7, Jack Nicklaus at 10, Anika Sorenstam at 12, Greg Norman at 15. Rory McIlroy, who won the 2011 U.S. Open at age 22, started golf at 18 months! His father, once a scratch golfer, started Rory on the game. At age 13 Rory joined the Golfing Union of Ireland's "coaching panels" for higher performers, and at age 18 turned professionalNo doubt about it: the younger the better. But then someone always says, yea, but what about Larry Nelson and Calvin Peete?

And, in 2009 a 37-year-old South Korean, Y.E. Yang, beat Tiger Woods for the PGA Championship. Up to that point Woods had never lost a major when he entered the final round with the lead. Remember, Woods started golf at 2. Yang started playing at age 19. In fact, Nelson, Peete and Yang are not the latest starters to achieve top level golf. Three prominent late starters were Frank Conner, Ellsworth Vines and Walter Travis. Henry Ellsworth Vines, Jr., (b. September 28, 1911, d. March 17, 1994) was an American tennis champion of the 1930s, the World No. 1 player or the co-No. 1 for four years in 1932, 1935, 1936 and 1937, able to win Pro Slam titles on three different surfaces. In 1942 at age 31, he became a professional golfer. Over the years he had a number of high finishes in tournaments, including at two professional victories (1946 Massachusetts Open, 1955 Utah Open) and a semi-final position in the prestigious 1951 PGA Championship when it was a match play tournament. He was twice in the top ten of golf money winnings, and one author wrote "he was surely the best athlete ever in the two sports." Frank Conner, born in 1946, played in the United States Open Championship in both golf and tennis As a youth, tennis was Conner's game. He didn't take up golf until he was 24 years old (1970) and turned professional the following year. Before that, at San Antonio's Trinity University, he was an All-American in tennis. He won the National Junior tennis title at 17, and played in three U.S. Tennis Opens. After switching to golf Conner failed 4 tries at Q-school; during this period he supported himself teaching tennis and playing mini-tours in Texas. On his 5th try at Q-school he got his card. He initially had little success on tour, reportedly making just $40,154 his four years on tour. Then in 1979, he finished in a tie for second in the New Orleans Open, one stroke behind Hubert Green. He led the 1980 IVB Philadelphia Classic after three rounds (won by Doug Tewell). He tied four others in the 1981 Quad Cities Open, but lost to Dave Barr in a playoff. He played in the 1981 U.S. Open, where he tied for 6th place (winning $9920). In 1982 he led the Sea Pines Heritage Classic after three rounds, but Tom Watson caught him and beat Conner in a three hole playoff. He did win a non-PGA event: the 1982 King Hassan Open in Morocco. He did wihn the 1988 Deposit Guaranty Classic. It was an official money even but not an official win on the PGA tour at the time, possibly because it was played opposite the Masters Tournament. He played on the Ben Hogan Tour 1990-1991, and won tiwce in 1991, sufficient to rejoin the PGA tour in 1992. In 1996, at age 50 he joined the Senior PGA and played on that tour until 2002; he came in 2nd in 1997 and 1998 contests. The distinction for oldest late starter to achieve golf greatness belongs to Walter Travis (1862-1927). A native of Australia, Travis emigrated to the U.S. at age 23. He was a cyclist and tennis player before taking up the game of golf at age 35. As noted in The Golf 100: Ranking The Greatest Golfers of All Time, Travis"knew he would have to develop a short game to succeed as a competitive golfer...He taught himself a reliable swing that produced limited length but great accuracy. Within a short time he was better than the players at his home club. He entered the U.S. Amateur at the Morris County Golf Club in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1898, his second year of golf, and reached the semifinals." Travis won the U.S. Amateur in 1900, 1901, and 1903. In 1904 he was ranked the best amateur player in the U.S. That year he traveled to Great Britain where, at age 42, he won the British Amateur. In 1979 he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. As noted in his WGHF biography: There has not been a golfer who played so well after starting so late in life as Walter J. Travis. Here was a man who didn't hit his first golf ball until he was 35, yet one month later he won his first tournament and two years later he reached the semifinals of the U.S. Amateur. Within four years of picking up a club for the first time, Travis won the first of three National Amateurs. He also was the first American citizen to win the British Amateur and ended his career, at age 53, by winning the prestigious Metropolitan Amateur in New York. In fact beginning to play golf after the teenage years is way outside the norm for top players. And those very, very few who did start outside their teens made up for the late start by utilizing Secrets 2 and 3. You can extrapolate this rule for all golfers. The later the game is taken up, the less chance one has to become good at it. Define "good" anyway you want: the later you start the harder it will be to get there. Starting young imprints muscle movements that stay with you forever, like riding a bicycle. Starting as an adult makes it much harder, if not impossible for most people, to imprint the proper muscle movements for an accurate, repeatable swing. When you start late the movements have to be learned mechanistically, and thought about in the performance. Top golfers did not learn the swing mechanistically, and don't think about mechanics when hitting the ball; for them, the necessary mechanics were imprinted in their central nervous system when they were still growing. Has no one ever become a scratch golfer starting the game in middle-age? I am sure some people have. One person even wrote a book about it: From Hacker to Hero in 12 Months, by Michael D. Oliff. The self-promotional blurb on the book's Amazon.com web site states that: "in this modern day fairy tale...Dr. Oliff, a top management coach and transformation guru...recounts his incredible one-year journey from a 26 handicap to a scratch golfer. In it, he challenges the fundamental approaches and assumptions of learning to play the game of golf from the unique perspective of a student learning the game and a renowned teacher able to critique it." The book is out of print but available from resellers via Amazon.com. I was able to obtain a used copy. One might think, from the promotional blurb, that Oliff discovered some 'short cut' or 'incredibly simple swing tip' like the ones touted in infomercials. But his "secret"? I'll let him tell it, in the following excerpts from his book. At the time of his "transformation" Oliff was 43 years old and self-employed as a management consultant. He started his magical year in January 1998. "During 1998, I dedicated six months full time and another six months part-time to improve my golf game from a twenty-six to scratch...suffice it to say, "full time" meant six days a week, twelve hours per day of ball striking while "part time" involved eight hours of effort three days per week." Oliff hit thousands and thousands of balls. Played hundreds of rounds of golf, often

72 holes a day. He took many lessons and read a lot of books. This incredible

amount of work (probably unprecedented), along with what I assume is a fair

amount of athleticism, gave him the enviable result. As you will see,

Michael Oliff's story corroborates my 'golf secrets'. He may have started late, true,

but his achievement was possible because of secrets 2 and 3.

Natural talent is comprised of four factors.---> Excellent visual-physical perception, or the ability to obtain desired direction, distance and speed of the ball by precise muscle movement. This means you know just how hard and in which direction and at which angle to swing the club so the ball will go where you want it to. This is same skill that allows an NFL quarterback to throw a pass so that the ball ends up exactly where his receiver will be several seconds later. However, it is also the same skill used by anyone driving a car when they apply brake pressure to stop just 2 feet behind the car ahead. In theory, if you can drive a car you should be able to gauge how hard and in what direction to hit a golf ball. This innate ability does surface on occasion in mediocre golfers. In the best golfers, it is evident on almost every shot.---> Excellent hand eye coordination. This talent is essential to coordinate swinging the club so it contacts the ball where you want it to on the club face. You may know how hard to swing the club because of good visual-physical perception; hand eye coordination makes it possible for the club face to actually hit the ball where you want it to. (Note that one can have excellent v-p perception, but whiff the ball because of poor h-e coordination.) This is the same skill that allows a baseball player to hit a ball coming at him 90 miles an hour. But it is also the same skill that allows you to catch a softball or even pick up a carton of milk or a piece of paper. Absent a major neuro-muscular problem, we all have some degree of hand-eye coordination. The best golfers have it to near perfection. ---> Mental fortitude. This is essential for you to keep v-p perception and h-e coordination at optimum performance, despite inevitable screwups on the golf course. All golfers suffer adversity while playing: bad shots, good shots but bad bounces, or just plain bad luck (e.g., landing in a fairway divot). Hard-to-define mental fortitude allows emotions to be kept in check, so that whatever happens while playing will not affect v-p perception or h-e coordination. In other words, not adversely affect your golf swing, your attitude, your game. ---> Good physical condition. This includes both overall muscle strength and aerobic physical fitness. PGA players can hit the ball longer than LPGA players because men have greater upper body strength than women. The stronger you are the harder you can hit the ball, but as we all know strength doesn't count for much around the greens or when putting. There is obviously far more to golf than pure physical strength, but without good muscle tone you are apt to become fatigued just swinging the club. Good physical condition is important to the game, even more than many amateurs realize, because golf is an athletic sport. Being "in shape" keeps you from becoming fatigued after walking and swinging a club for several hours (which can happen even if you ride a golf cart). There is not much you can do to improve your innate talent. Some people are born strong, some weak. Some have genes for athletic endeavors, others don't. Some people are forever klutzes and even though they start the game early, never excel, then lose interest and drop out. Some are naturally able to stay focused in the face of adversity, others collapse and lose control at the first blunder. No doubt mental fortitude is important, but not nearly as important for most

golfers as professionals like to preach. The concept has received tremendous emphasis over the past decade, because of the very fine line separating all the touring pros.

In 2010 Tiger did not win a single tournament. In 2010 the low scorer on the PGA Tour, Matt Kuchar, had an average score of 69.61 over 97 rounds. Seven players were tied for #96, with an average score of 70.95. Player #103, DA Points, averaged 70.96 over 90 rounds, a difference of only 1.35 strokes from #1! Think about that. The average score difference between #1 and #103 over a full year was less than 2 strokes, Considering a tournament is 72 holes over 4 days, it's easy to see that any of these players could win in any given week. What separates them out? Well, the mental side is a big factor (and putting is often another). Who stands up well under pressure, who can recover from a bad shot, who can stay focused down the stretch when the game will be won perhaps by a millimeter on the putting green -- yes, mental fortitude can make a difference between winning and losing. Books by sports psychologists, such as Dr. Bob Rotella, have become very popular. Dr. Rotella's titles speak to the mental game: Golf is Not a Game of Perfect and Golf is a Game of Confidence. But understanding that golf is not a perfect game, and is a game of confidence, doesn't count for much if you lack a repeatable swing. Lack of a proper mental approach on the course is not why most mediocre players are that way. Average or mediocre players are the way they are because they don't know how to set up and hit the ball well, on a consistent basis. Scores are high largely because of v-p mistakes, h-e miscues, and lack of experience. We all make so-called mental errors while playing, but by and large they are minor compared to errors in the game's fundamentals: grip, alignment, stance, ball position, back swing, down swing, follow through. I have seen dysfunctional, immature players post low scores. They blow up on a bad result, throw their clubs, castigate some mystical golf god for an errant shot. Their golf immaturity (for want of a better term) might certainly keep them from winning tournaments, but the swing they learned in childhood does not wilt on the course. John Daly is perhaps the best example among recent PGA players. Periods of mental instability (by his own admission, related to alcoholism or alcohol withdrawal) kept him from contending in many tournaments following his 1995 British Open victory, and ultimately led to loss of his regular PGA tour card. However, his basic swing wasn't affected; he could always strike the ball well because that ability was learned (and imprinted) as a youth. Once learned, that skill doesn't go away. On the other side of the coin I have seen the most mature, easy going guys -- people who never let a bad shot derail their game, who stay focused through 18 holes -- duff, slice, shank and otherwise destroy shots they are occasionally capable of hitting. But their swing was not grooved and therefore not repeatable, and the ball simply went where they hit it. Yes the mental side is important, but judging from everything you read and hear, its importance is way overblown for the average player. All the mental training and mental focusing in the world is not going to convert a bad swing into something else, or a bad player into a good one. When someone says (and you will hear this often) "golf is 90% mental and 10% physical," they are using hyperbole to emphasize a point that applies only to the most skilled golfers, players who have the talent and ability to hit just about any golf shot. When you hear such a statement, what the pontificator really means is something like this: 'You know, given the superb skill levels of the pros on tour -- where everyone can reach greens in regulation, and any individual can win on any given day -- attitude and mental toughness play an important role in the game. In fact, among really good tour players, the ability to stay focused and not get ruffled is what often separates winners from losers.' THAT's what the mental advocate means (or should mean). So certainly, be aware of the mental side; a bad attitude, inability to stay focused, a feeling that the golf course "owes" you something -- these things can defeat you before you start to play. But chances are, if you are struggling with golf, poor psychology is not what's wrong with your game. It's swing mechanics.

Is there any hope at all in the area of innate talent? A little.

Plenty of people start playing young, but not many emerge like

I have no patience for ads and articles that promise near perfection "for those without time to practice," or push a gimmick "so you too will learn to hit the ball straighter and longer - guaranteed." Nonsense. The more you practice hitting a specific shot in a proper manner, the better your will be for that shot. All top golfers (well, almost all, anyway), practice, practice, practice. Butch Harmon once said on the The Golf Channel that Tiger Woods "practices more than any other golfer I know." Let that sink in: the world's number one player at the time of Harmon's comment practiced perhaps more than any other golfer.By 'some type of tutelage', all I mean is for someone to show you how it's done. Doesn't have to be a golf pro, either. Could be your parent, your older brother, a friend, whoever. Many top golfers (e.g., Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Lee Trevino) started out as caddies, and in the beginning simply emulated good golfers they worked for. Y.E. Yang taught himself correct form by watching instructional videos (reportedly one by Jack Nicklaus). Along the way they picked up pointers and practiced, practiced, practiced. Start young enough, with enough talent, and all you need is another player whom you can emulate, who can show if you're doing something wrong or how to do it right. All good golfers learn this way. The first person emulated may be a professional, but more often that is not the case. While it is rare for a top golfer to be completely self taught, you don't need to learn from a professional to become an excellent golfer (providing you start young, etc.). And what do top golfers practice? Dozens and dozens of different shot types they will

encounter on the course. The typical amateur may never practice, or if he/she does, just

hit a few dozen balls at the driving range, often tee shots only. Ask a weekend golfer who

professes to practice -- what types of shots do you hit? Likely it will be the tee shot with

the driver, a few long iron shots, some short pitches and some chipping and putting.

And all from level lies. These are

your basic bread-and-butter shots, true, but they ignore dozens of variations - seldom if

ever practiced (and never to perfection). Look at just a few of the shots top

golfers practice over and over and over.

Counting all the variations, there are at least 100 different shot types in the above table, and this is only a partial list of what you will encounter playing golf! But the weekend golfer thinks only of the four basic shots in practice (drive, pitch, chip, putt). He or she hits a few desultory golf balls on the range, then wonders why his/her score is so high on the course. One reason is that more than half the shots encountered on the course have never been practiced! (It is somewhat like playing Beethoven's Fur Elise really well in piano practice, then stumbling over the Moonlight Sonata before a live audience; if you never practiced the Moonlight, why should it come out well?) I first posted this essay in 2001, based on my own observations.

Although it has been revised with new data and links, the essential

'secrets' are the same now as then. Thus it was gratifying to see academic

research and a popular book published in 2008, essentially validate my own

observations about starting early, natural talent and "practice, practice, practice."

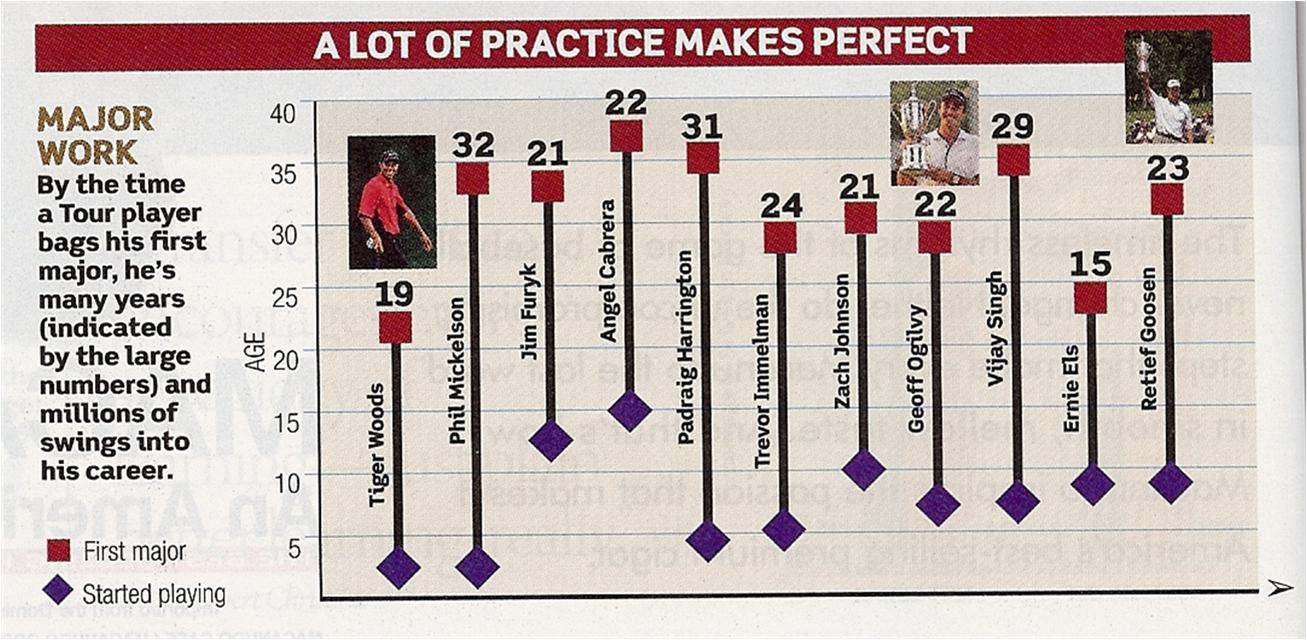

To show just how important is the concept that 'to get good you need to start early and have thousands of hours of practice', it was finally mentioned in a popular golf periodical, the September 2009 issue of Golf Magazine. Golf Magazine and its chief monthly competitor, Golf Digest, routinely publish 'get good quick' articles that simply ignore the concept of what it takes to be a skilled golfer. In this particular article the magazine quotes Ericsson's research and even provides a graph of its own, shown below. Each vertical bar shows the age at which the golfer began golf and the number of years before he won his major tournament.

Golf Magazine and all other popular periodicals continue to ignore or underplay the concept of starting early and intense practice for their target audience, us. They instead sell the fantasy that all you have to do is change this maneuver or stance or hand grip to revolutionize your game. The cover of Golf Magazine blares: "Hunter Mahan's 5 go-to moves: CLUTCH SHOTS MADE EASY." Yea, for Hunter Mahan. No where in the intruction was it recommended to 'practice my moves 1000 times and you might get it right.' My 3 secrets of top golfers may seem so obvious, but what do they have to do with the average golfer, the weekend player? Just this: The average golfer may not understand why he or she is stuck in a rut, and is often made to feel (by friends, or the media, or even some teachers) that this or that maneuver, this or that driver, this or that lesson will magically improve their game. Which, of course, is nonsense. Tell me the last time you read the truth in a golf magazine, or saw it discussed in mass media publication. Do you read, "Hey Mr. Middle-aged golfer, there's not much hope for you, you klutz. You started too late, you don't have any talent, and you don't practice enough." Of course not. What you read instead (month after dreary month) is "Cure Your Slice!" "Take 12 strokes off your game!" "Hit it further, longer, straighter." "Guaranteed to lower your handicap." "Clutch shots made easy." Yes, the word "practice" will be mentioned occasionally, but not with any emphasis on the truth, which would require the following DISCLAIMER:

Unless you practice this shot at least 30 times a day for a month you won't get it. And if you get it, the shot will still not lower your score because there's dozens more shots you need to practice. What is the most perverse part of media hype is that no golf tip can possibly apply to any sizable percentage of the audience. People come in all shapes and sizes, all ages, infinite degrees of skill and capability. Even among the top players of the world, every swing is different (even though the overall results may be similar). Obviously, any particular piece of advice about swing movements is apt to apply to only a minuscule percentage of golfers, but the reader (or viewer) has no way of knowing if it can apply (and therefore help) him or her. The popular golf media with all its hype does not represent the real world, which is the world where the three 'secrets' govern who is good in the game. The best (and most painful) way to learn these secrets is the way I did -- a long struggle to revealed truth. That takes time, money (lessons, lot of playing), and most of all persistence. At some point you will hit a wall and wonder 'Why am I not getting better?' Easy: you started too late, and/or you don't practice enough, and/or you don't have enough talent. The second way is to learn from others who write honestly about golf. Honest writing is found in books by non-professional golfers who have struggled with their game. (Not that professionals don't write honestly about golf; they just don't reveal the secrets I have stated.) Quoted below are two books I heartily recommend because they exemplify the secrets.

Breaking 80: A Journey Through the 9 Fairways of Hell, by Lee Eisenberg

* * * Yes, learning golf is like learning a musical instrument.

If you have no musical background, and you

start to learn an instrument -- piano, for example -- at age 30 or 40 or 50,

there is little (no, zero)

chance of becoming a concert pianist. Why? You started too late.

But if you have innate talent,

and practice a lot, you might become a passable player, for your friends or family,

or just for yourself. But you won't become a musician. You started too late.

But suppose you start at age 5 or 6 or 7?

You can become very good, providing you also have

some innate talent (without which you probably wouldn't stay with the instrument in any case)

and you practice a lot. Will you become a Mozart or a Rachmaninoff? Of course not. Musical

genius is like athletic genius.

Tiger Woods had the three requirements all lined up.

He started the youngest; he hit the most balls, and he had the most talent

(all nurtured by his father; same for Mozart).

Mozart died at age 35.

Had he been kept from music until, say 25, he would not have developed

into the one of the world's greatest composers.

It takes the formative years to develop the skills

that make golf or music come easy.

And unless it comes easy you won't become good at it.

There are many superb athletes who took up golf

relatively late and who did not practice much

but who in later life aspired to become professional golfers. Three examples are

Michael Johnson (basketball),

John Elway (football) and Ivan Lendl (Tennis).

Let's look at their profiles

World's top male basketball player for a decade; first took up

golf in college (introduced to game

Age at start of golf playing: a little too late

Natural talent: cannot be faulted; has it in spades

Number of golf balls hit: not enough, because he was always shooting a basketball

Age at start of golf playing: too late

Natural talent: cannot be faulted; look at his tennis game

No. of golf balls hit: not enough, because in his youth he was always hitting tennis balls

One of world's top football stars, took up golf seriously

after retiring from Denver Broncos. A regular on the

Celebrity Tour, has a handicap of 3.

Age at start of golf playing: too late

Natural talent: huge

No. of golf balls hit: not enough, because he was always

throwing a football

Each of these sports superstars has one of the necessary

ingredients to be a top golfer: innate

talent (v-p perception, h-e coordination, mental toughness, and physical conditioning) that

brought them to the pinnacle of their professional careers. But then why can't they become

regular tour players? Because in golf they can't hold a candle to, say,

Fred Couples. Couples

is about their age and has won numerous golf tournaments including the Masters, even

though he can't run as

fast as Elway, jump as high as Jordan, of swing as hard as Lendl. He doesn't need to.

He's got the innate talent, plus he started young (turned pro at age 21),

and hit a lot of balls in his lifetime. It all comes down to that.

Wait a minute, you say, Jordan's a 6, Elway's a 3, and Lendl was once a zero handicap. That's superb - for an amateur. But they would be better had they started young,

hit more balls, etc. Each of them could probably have become a professional golfer.

More importantly, the principles that keep them from becoming professional golfers

now are the same principles that keep most of the world's golfers from

becoming (in their own estimate) either 'good' or 'better' players.

The same principles that keep hackers, say, from ever breaking a hundred, or a mid-20

handicapper from reaching 18, or a 10 handicapper from going to a 5: starting too late

in life, and/or not hitting enough golf balls, and/or insufficient talent.

This is suppose to make you feel good? Who wants to read a golf article with such a

negative theme? Well, here's the positive side. Once you accept these secrets or

truths, you will have a solid foundation to begin improving your game.

More importantly, you will (or should)

a) feel better about your game because it will be in proper perspective and,

b) have a realistic chance of improving - perhaps enough to truly

increase your enjoyment of golf.

You will not become a pro or a top amateur from anything you read here, however,

and that's a promise.

I said there was a fourth secret, and it is this:

The 'top golf teacher' is a perverted myth of sorts.

Tiger Woods

didn't have a 'Top 100' golf pro teaching him when he was a kid; he had his father.

Ditto

Arnold Palmer,

whose father was a greens keeper and club pro at Latrobe County

Club in Pennsylvania. Woods and Palmer had top fathers, who a) got them started playing

before they ever went to school, b) nurtured their kid's innate talent, and c) made

it possible for them to hit tons of balls and play competitively at an early age.

All things undeniably important, but the 'teaching' aspect is not why these players

became great. In fact, apart from his father's early instruction, Arnold Palmer

never took any golf lessons.

Going back much further in history, many of the great golfers had no teacher at

all, they just learned by emulation. One good example is

Francis Ouimet, a legend in golf who won the U.S. Open in 1913.

An article by John Paul Newport -- Top Pros Who've Never Had a Lesson -- in the Wall Street Journal May 14, 2011, is a must-read for people who (mistakenly) think teachers make the golfer. "Bubba Watson, with two PGA Tour wins already this year, leads the FEDEX Cup points race and is second on the money list.

Good teachers facilitate 1, 2 and 3, or at least don't stand in the way.

Mostly, good teachers facilitate 2 and 3, nurture talent, help show

what shots to practice, how to do it most efficiently, etc. Does anybody really think

coaches Butch Harmon and Hank Haney made Tiger Woods the world's greatest golfer?

More often it seems the top golfer makes the reputation of the teacher, not the other way around.

Still, top coaches probably deserve credit for the incremental improvement in the games

of some players. I believe top coaches like

Butch Harmon,

David Leadbetter,

Jim McLean,

Charlie King

and others can take a top player who is at perhaps

95-96% of his/her game and --

with much practice on the player's part -- help increase their performance

to perhaps 97-98%. This slight increase in performance may make the difference between winning

and losing a tournament or two. But recognize that the top coaches are

starting with top players who then work very

hard at the game (which for them, after all, is a profession). Lesser effort by

lesser players, even under the guidance of a good professional,

likely won't have the same result.

I don't minimize the role of the teaching professional for the new or struggling

golfer. In fact, for people who didn't approach golf via secrets 1, 2 and 3, golf

lessons from a professional are highly recommended. After all, you have

to make up for lost time, and as an adult is not the time to start the trial and

error method (if you want to become good, that is).

Usually the person who takes up golf without benefit of

1, 2 and 3 doesn't even know where to start or what/how to practice, or anything about the

game. So I believe some golf lessons are invaluable for anyone taking up the

game as an adult.

Golf lessons are of little help if they aren't followed by practice, to groove muscle memory or whatever you want to call it. Lessons without practice to perfect what you've been taught is never helpful. Golf's like music. Take a piano lesson, then come back a week later for another lesson without having practiced, and your teacher will know instantly. You've learned nothing. The simple truth is that adults who take up golf invariably try to learn the game in a manner never used by the top golfers. We try to learn by studying the game. We take lessons, read books and magazines, watch The Golf Channel. But...the pros didn't learn golf that way!The pros didn't study golf as youngsters, just like we didn't study how to ride a bicycle as a kid. (JackNicklaus has stated he never read a golf book except the ones he wrote.) We learned to bicycle by trial and error, and that's how the pros learned to play golf. Their teachers may have facilitated, honed, channeled talent, but it still comes down to 1, 2 and 3.

Now a few paragraphs about golf equipment -- one of the greater golf myths. Golf equipment is better than ever (more durable, lighter), yet golf handicaps aren't any lower as a result. The average scores on the top amateur tournaments have not fallen in the last 20 years. Some of this could be due to tougher course design, but it's also a fact that across the land, there is no evidence that better equipment has improved the average players' scores. Yet the myth is that the latest driver, with its humungous head size, or the newest wedges, with their titanium heads, or the sleekest putters, with their exotic inserts, will somehow "transform" your game. More nonsense. The worst claim of all is that "now, you can buy a better game." This is the mantra of the equipment manufacturers, and the media they advertise in, because obviously they want to keep selling new equipment. And we buy, buy, buy (and by "we" I mean me, too). But the fact is, beyond a certain point (which I'll discuss in a moment) the latest in equipment won't improve your game -- unless you're playing with mis-fitting clubs to begin with. Like "mental fortitude" discussed above, emphasis on the newest and jazziest equipment is an oversold concept to becoming a better golfer. (Tiger Woods could beat us with a frying pan, shovel and pool cue, as in the movie Tin Cup.) So what's important? Equipment should "fit" the golfer as to length, weight, and "feel". There is also something to be said about proper lie angle (angle of the hosel or shaft of a clubhead in relation to the sole of the clubhead), shaft flexibility (stiff, regular, light), and material used in the construction of the clubs. In fact, club design can become very complicated, the more you get into it. The result is some controversy about whether one should buy 'off the shelf clubs' or get a set 'custom fitted'. There are a lot of variables in this discussion. The weekend golfer doesn't have the luxury of trying out clubs for free until he/she finds what works best (like professional golfers). The amateur is stuck with what he/she gets, whether custom fitted or store-bought. But what works in the store may not work as well on the course. On the other hand, there is no guarantee that 'custom fitting' will be done competently. However, there is also no doubt that, if you are serious about the game (i.e., want to play your best, and to improve) you should not buy golf clubs without swinging them first, or without someone knowledgeable (hopefully a sales person, but better yet a PGA professional) checking to make sure they 'fit' your swing and body size. Reasonable investigation of clubs (including trying them out) in a retail store or some other venue should allow you to find a comfortable, ready-made set. On the other hand, if you have great faith in a particular club fitter, and you can afford it, by all means get a set custom fitted. In any case, DO NOT be influenced by ads featuring famous golfers. They NEVER play the clubs they pitch to us (they may play the manufactur's brand, but understand that the clubs they use are custom-manufactured to exacting and unique specifications). Furthermore, professionals change or modify their clubs all the time -- and for free. On the other hand, most amateurs are more or less stuck with the set they buy (unless they trade in for a new set). So what is really important? First, golf clubs should be durable (e.g., the club heads don't bend or dent when you hit the ball), which precludes the 'starter set' sold in stores for a hundred or so bucks. For a new set of irons and woods (12-13 clubs), one probably needs to spend a minimum of $500 for a store brand. For a name brand it will be more like $1000+ (not including putter, which is another $50 to $100+). Used clubs are fine, but should be bought with some knowledge of their quality and durability. Second, golf clubs should be the right length for the individual, which means at least trying them out before buying (I have seen mens' clubs used by a short woman -- big mistake). Third, clubs should not be too heavy or too light (generally, all woman's clubs contain graphite shafts, and this is popular for men also). Fourth, golf clubs should feel comfortable to the user. It's like trying on a new pair of shoes. You 'know' when they feel comfortable. All this simply means trying out clubs in the store (or other venue) before you buy. Ideally, a knowledgeable person should help assure that they clubs 'fit' your swing, but this does not mean they need to be custom-fitted. A swing tryout in the store won't be the same as playing 18 holes, but at least it should help avoid an obvious mistake. For most people, a modern set of golf clubs will include cavity-backed irons with graphite shafts, woods that include a driver with a 400+ cubic cm head, plus a 3-wood and 5-wood (and a putter). Once you've obtained a set of comfortable clubs, of the right length and weight and that feel good for you, then you can ignore all the hype about the newest, latest, etc. If you have a comfortable set of clubs, whether they cost $500 or $2000, buying the latest hype won't improve your game. Why not? Because scores are what they are because of grip, alignment, swing mechanics, etc., not nuances of club design. Such nuances only matter to professionals, who must squeeze out every possible advantage on the course, and so cannot afford the slightest fitting problem or error in lie angle or minuscule change in swing weight. For professionals, every yard or foot can make a difference in a tournament. Let's say you get the latest, biggest driver. You might hit it further, but so what? Another 10-20 yards is not going to lower your score; it could even raise the score if you slice or hook the ball. You will just slice or hook it 10-20 more yards further from the fairway! Many high handicappers would in fact be better off not using their driver, and teeing off with a 3-wood. A well struck 3-wood will go just about as far as driver, with a lot less side spin (and therefore less tendency to slice or hook). How about the latest "spring loaded" (and non-USGA approved) driver? Tempest in a teapot for the average golfer. Won't matter. How about the latest, greatest putter? It will more than likely not improve on your ability to putt, assuming your current putter is comfortable for you. In fact, the dozens of putter brands and hundreds of putter designs is testimony that there is no one best putter, and that you just have to find one you are comfortable with. It doesn't hurt to experiment, but don't expect to lower your score because of the newest mystery metal insert. So, sorry to bust the manufacturers' bubbles, but their equipment ads (promising longer distances, more accurate shots, lower scores) are largely wishful hype. I know. I (and countless others) have fallen for the hype on numerous occasions and bought items that had zero improvement effect. Assuming you have a decent set of clubs to begin with, you won't play better or lower your scores by responding to these ads. Durability and comfort (which includes proper length and weight) are all that matter for the vast majority of golfers. Lee Trevino -- one of the most direct and honest-speaking professionals who ever walked the course -- said it best: "It ain't the arrows, it's the Indian." Right on. And the golf ball? You think your score will be lower with balata this or wound that?

With a soft or hard feel? Pure advertising. Doesn't matter. The golf ball is not

shanked because it is brand X vs. brand Y. The ball doesn't go in the water because it

is double or triple layered. The ball

doesn't travel 20 feet past the cup on a 10 foot putt because it contains titanium or

any other ingredient. Play with a clean, non-damaged ball, and don't

pay more than $1.50/each for new golf balls. They are always on sale.

More expensive won't matter.

Now a few words on course management.

Golf is an infinitely complex game, and the role of course management can't be

minimized. It means hitting the right club so you don't get into trouble.

If poor course management can decide a major tournament, imagine what it can do to a rank amateur's game. Like the mental side, bad course management is important, but at the same time it is not why players are bad or mediocre; instead, it is why scores on any given day may be higher than they need to be for a particular golfer. Every player -- no matter how mediocre -- should realize his or her probability of shot making; such an understanding can only help improve one's score. For example, it is certainly stupid for an amateur to hit a 3 wood to a green two hundred yards away if the green is surrounded by water and there is a 1% chance of pulling off the shot; a lay up would be smart, even if it's his 3rd or 4th shot on a par 4 hole. But if the player was better he would be only 150 yards from the green to begin with, or it would be his 2nd and not his 3rd or 4th shot. More to the point, good course management comes naturally to players who have the shot making skills, and is (again) not the main reason for high scores among amateurs. High scores come from not hitting the fairway off the tee, from missing the green 100 yards out, from not being able to get out of sand or over water, from 3 and 4 puttting -- in short, from bad swings and errant shots. So yes, course management is key, but I believe it also comes naturally with play and practice (Secret 3); then you know what your skills are, what you can and cannot accomplish. Finally, what about grit and determination? I debated making that another 'secret', sort of like 'You can't get better unless you have grit and determination,' blah, blah, blah. But I did not, for two reasons. First, it is too vague. Too easy to say, 'yea, I have the determination,' when you really don't. Second, if you really have grit and determination, you would be banging lots of golf balls. So 'Secret 3' includes 'grit and determination'. If you have them, you will be banging tons of balls (or playing a lot, which is another way of doing that). So there you have it, my four secrets or truths about becoming a good golfer. Now you ask: How can these secrets help me become a better golfer? Simple. Realize them, then improve those aspects realistically possible. The 4 Secrets of Top Golfers and

|

SECRET |

COMPONENTS |

WHAT YOU CAN DO |

| 1. Start playing young | Nothing, if you're already an adult | |

| 2. Have Natural Talent | Visual-physical perception | Nothing |

| Hand-eye coordination | Nothing | |

| Mental side | Be aware of its importance | |

| Physical conditioning | Work out and exercise | 3. Hit a lot of balls | Learn proper technique for various shots | Take Lessons | Perfect various shots | 'Deliberate Practice' | 4. That's all there is | Avoid gimmicks, quick fixes and wasting money on fancy equipment |

As to starting young, there is nothing you can do if you started playing as an adult. If you are a teenager and reading this, and have a desire to take up golf 'in the future', go get some clubs and start NOW. The sooner, the better.

As to v-p perception and h-e coordination, they are like IQ. You can't improve IQ, but you certainly can study hard for a test and improve your score. So while the innate physical abilities you are born with can't be altered, by sheer practice you can definitely improve shot making ability (Secret no. 3).

Secret #3 covers the most obvious thing an aspiring golfer can do to improve. Practicing shots can certainly improve your enjoyment of the game, and may improve your handicap, especially if it is high to begin with. I wrote an on-line book just for the 'golf hacker' and high handicapper that discusses specific ways to improve: Why Are You STILL a Hacker? As you read my book, or any other golf book for tips, drills and other useful information, always keep in mind the four secrets of the best golfers.

Copyright 2001-2012

Last updated October 3, 2012

Lawrence Martin, M.D.

Return to Lakeside Press

|

OTHER GOLF WEB SITES by LAWRENCE MARTIN Why Are You STILL a Hacker? (An on-line golf book) Avant Garde Golfer - A golf journal of the future |